Whether it’s inserting revealing song lyrics in place of a username on MSN Messenger, living out personal relationships on Instagram, or immediately thinking “ooh, which publication could I pitch this to?” when something happens to me, I am a perennial “over sharer” and my primary medium for over sharing is online.

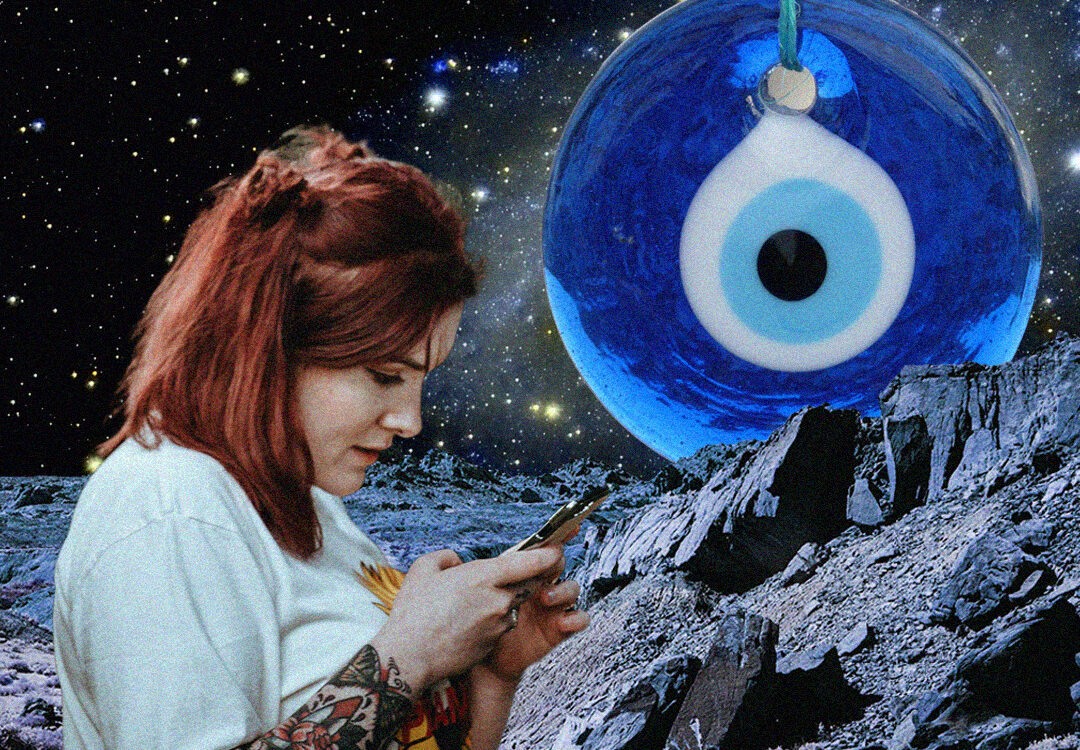

This is contrary to what my Middle Eastern heritage tells me is the correct way to conduct myself. Indeed, in Eastern cultures, there has long been a focus on privacy – in particular when it comes to good news. Termed ‘hasad’ in Arabic and ‘nazar’ in Urdu, it’s a widely-held belief that a mean or resentful gaze can cause harm or misfortune for the person, object or circumstance that is envied.

On social media, there is nothing but gaze.

The belief in hasad is contrary to our generation’s social media habits, in which many of us share pretty much our whole lives online, often curating our feeds and lives to elicit the most envy – whether consciously or not. Social media, and Instagram in particular, has traditionally been a place of filters and Facetune, somewhere to portray our good, better, and best selves.

In the before times, the way to win Instagram was with bikini selfies, expensive dinners and #hotdogorlegs in far-flung destinations. But over the last few months our worlds have shrunk and been brought into stark focus. Everything from how big someone’s house is to if they have outdoor space, who they live with, if they have disposable income and more has become something we are immediately more conscious of – and sensitive about.

In truth, before Covid and before lockdown, the differences in people’s circumstances were mostly billed as aspirational. It is this that facilitated the rise of the likes of the Kardashians and that paved the way for influencer culture. It’s all up for grabs, capitalism told us, the possibilities are all in your hands.

But there is an increasing realization that that is not really the case, that while we may be weathering the same storm, we are all on different boats – the size and shape and fortitude of which are often determined by things that have little to actually do with us. The foundations social media is founded on, then, have become, in many ways, superfluous – and much of the content we used to share and ‘like’ now feels insensitive and inappropriate.

It’s something I’ve been thinking about a lot lately, in particular in the moments where I’ve managed to carve out some semblance of happiness for myself, in the midst of this shit show of a year. Whether it’s a meal ordered on Deliveroo, a sunset viewed from my balcony or a socially-distanced park hang with my mother, when sharing any little joy, I am increasingly aware of those not currently (or ever) privy, and of the envy – and evil eye – that this may then elicit.

While it’s a concern that’s new for me, it’s something many have long grappled with. The second-season of the Emmy-nominated HULU show Ramy navigated this in an episode centering on Ramy’s sister, Dena (played by actress May Calamawy). After announcing her law-school scholarship on Facebook, Dena is criticized by her mum for sharing her good news on a public forum, warned that she’d now be vulnerable to the evil eye.

In an article for The New Arab, author Hafsa Lodi reported that 76% of 165 respondents of Middle Eastern and Asian origins said that it’s something they worry about, or at least contemplate, when posting on social media.

As Lodi outlines: “while some [social media users] add the distinctive eye-bearing amulet (a symbol culturally regarded as protection against the evil eye…) emoji to their captions, or type “#mashallah” (stressing that their good fortune is the will of God) in the hope that will cover them, others avoid posting potentially envy-inviting images altogether.”

Social media is the great connector, and it’s a tricky terrain to maneuver, in particular for creative millennials, or those who rely on it to promote their work. What’s more, in reality, anything can incite envy in others. Diminishing, or feeling the need to guard our own joy in fear of attracting the evil eye, is not really a nice way to live.

Giving ‘hasad’ too much consideration ultimately means that instead of believing in and living our lives with a mindset of abundance, we are buying into the principle of scarcity; the idea that if I have something, it means there’s less of that in the world for someone else to have. It’s a distrustful and depressing mindset I’m not keen to adopt. Despite the craziness of 2020, we must believe that there is enough joy, enough good to go around.

Indeed, there’s a balance between using social media to inform and engage with fellow users, and posting things in an exhibitionist fashion. Perhaps it’s finding this balance that is the key. In reality, it’s never a bad idea to tap into our intentions and be considerate of how what we do may impact others – both on and offline.