Last month Harvey Weinstein was sentenced to 23 years in prison for third degree rape and a first degree criminal sexual act, and people rightly celebrated justice served. Right now, it’s impossible to predict its wider impact on society and the legal system. What’s certain, though, is that one case won’t shift the culture that enables sexual harassment and violence to exist in the first place. These crimes are so finely woven through womens’ everyday experiences that it has taken a movement, a chorus of voices, to make people see and believe they happen at all.

Prosecutors at the trial in Manhattan worked hard to dismantle preconceived ideas of how ‘typical’ victims and perpetrators behave, and in turn dismantled the notion that sex crimes follow neat scripts. Jurors heard the central victims acknowledge they had maintained contact with Weinstein after they were attacked. One had a relationship with him, another exchanged emails. What’s striking is that the jury was able to understand that maintaining contact doesn’t negate a woman’s experience of sexual violence. It can seem nonsensical to people who haven’t experienced these traumas, but it’s common for victims to maintain relations with a perpetrator.

It could be for fear of losing a job, fear of further violence or manipulation, the result of shame and self-blame, or because people respond to trauma in different and often unpredictable ways. That there’s no cut-and-paste narrative for rape shouldn’t be a groundbreaking realization. But Weinstein’s conviction and sentence could hint that people are finally ready to believe and accept womens’ experiences in all of their nuance. This could, in turn, encourage prosecutors to pursue similarly challenging cases that might have previously been dropped.

In the UK, there’s a growing gap between the number of rape cases reported and those going to court – of the 57,882 reported cases of rape made between 2018-19, just 1,925 resulted in conviction. One of the key reasons for this, according to the Crown Prosecution Service, is that cases are becoming increasingly complex. This is partly because complainants are now reportedly routinely asked to grant full access to their digital devices and personal information. A Guardian investigation also found the CPS may have “raised the bar” on the cases it charges in order to improve the look of its performance data. These findings, along with the troubling prosecution statistics, led UK campaign group End Violence Against Women Coalition to launch a judicial review challenge against the CPS, describing its current practise as “the effective decriminalisation of rape.” The High Court refused the group permission to bring the case.

“It’s terribly disappointing that this complaint wasn’t upheld because in a way, you get these three steps forward and two steps back,” says Pip Eldridge, Interim Director of TIME’S UP UK. “We always say our system in the UK is so much better than in the US, but if this is happening, if there’s a mass cover up, we have a real issue.”

Weinstein will soon face four further charges of rape and sexual assault in Los Angeles, but there’s little chance the Manhattan indictment will legally affect the outcome of this second trial. That’s because the federalised court system in the US gives each state the power to make its own laws and decisions. It’s likely, though, that the intensive media coverage of the case and its central role in the #MeToo movement will have impacted jurors’ preconceptions. Another possibility is that the precedent set in Manhattan will radiate across other US states – regardless of whether or not juries are obliged to consider it.

“I think there will be powerful ramifications when you have a precedent of that status in law,” says Eldridge. “The influence Weinstein wielded was legendary, so the idea that someone with this degree of immunity can be brought to justice will also act as a deterrent for men who, according to Weinstein, are ‘confused about these issues.’ Gloria Allred summed it up perfectly when she said that ‘for any man who’s confused about what sexual harassment is, you just have to look at this sentence.’”

The high-profile nature of this case will hopefully embolden more women to come forward. And yet brave accounts of sexual violence are continuously met with harsh reality checks from a society that still sees survivors as ‘damaged goods’. In February, the singer Duffy went public with her experience of being drugged, held captive and raped earlier in her career. This month she went into greater detail, explaining that it was a male friend saying “most men would run a mile if they knew you were raped” that triggered her decision to speak out. After the post went live, “Duffy lying” became the third highest result in Twitter’s auto search of her name.

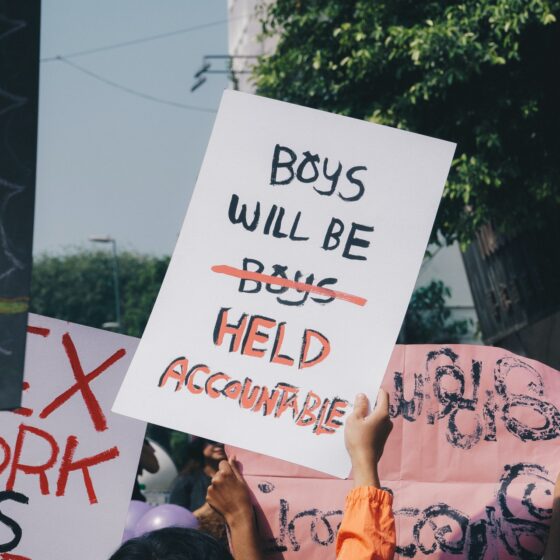

Fear of not being believed is stopping women from speaking up. One in four young women in the UK fear being fired for reporting sexual harassment at work, and at the moment employers have no duty to prevent the crime. Instead, the approach is reactive and puts the onus on the victim to complain. A 2016 TUC report found that more than half of women are sexually harassed at work, but calls for change fell on deaf ears until the #MeToo movement began later that year. The government was forced to listen, and in 2019 it launched a consultation into the laws around sexual harassment at work.

“It’s not right that under current law there is no legal duty on employers to take proactive action to prevent sexual harassment happening in their workplaces,” says Sian Elliott, women’s policy lead at the TUC. “We need a change in the law that would make employers responsible for protecting their staff. This would shift the burden of tackling sexual harassment away from individuals and drive the collective change needed to end sexual harassment at work.”

“Alongside this, we want the government to reinstate workers’ protections from third party harassment and to extend the time limits for employment tribunals that prevent women from accessing justice.”

Weinstein’s sentence shouldn’t be seen as a full-stop at the end of #MeToo, then, but a reason to shout louder for change. This change needs to include all women if its goal is to end sexual violence. Women of colour, trans women, indigenous women, queer people, and asylum-seeking womens’ experiences sit in the context of extra layers of discrimination and oppression, and yet their stories are left untold. #MeToo has proven that sex crimes happen in Hollywood, but justice now needs to shift beyond the white celebrity lens.

For asylum-seeking women, for example, sexual violence often intersects with insecure housing, racism, domestic violence, and emotional and financial abuse. “A lot of the women who come to us are facing homelessness and issues around their visa. They need a roof over their head before they even think about anything else,” explains Camille Rouse, Legal Advice Service Manager at London Black Women’s Project, a specialist organisation for black and minority ethnic women and girls. “It’s only once those issues are addressed, and through further discussions, that we find out they’re experiencing sexual harassment.”

And when these conversations do happen, the organisation has found there’s nothing available for the women they support. “These women are not going to call the police as they’ll just question them for working illegally, they’ll pass on details to the Home Office,” Rouse says. “We’re constantly trying to figure out ways in existing legislation to take those cases forward, but that would mean it’s not identified as sexual harassment as such, it’s identified in other ways. It’s been a huge struggle for us to identify gaps in the law when, actually, there is no law or framework.”

Legislative change is a slow-moving process that relies on raising consciousness across communities and institutions, and #MeToo has made that feel possible. “People’s hearts and minds are changing,” Tarana Burke, the founder of the movement, said at last year’s Time 100 Summit. “We can shift culture if we work in unison.” But right now, for everyday women, the message is this: everything has changed and nothing has changed. Change is contingent on people interrogating their own beliefs and holding others to account. Weinstein’s conviction and sentence is just the beginning of that arduous journey.