Content Warning: Please be aware that this article contains references to domestic violence, sexual violence and abuse.

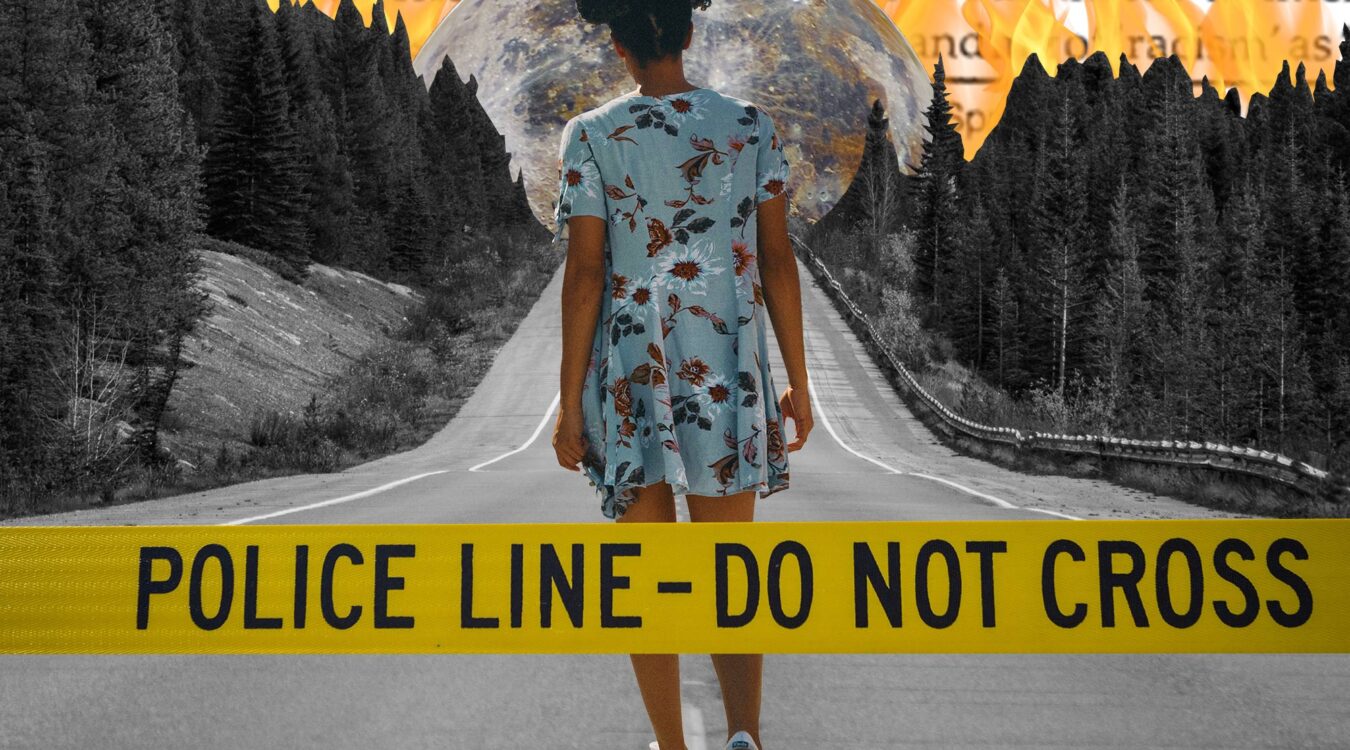

On the 6th June 2020, 19-year-old racial justice activist Oluwatoyin Salou tweeted that she was molested. She went missing the same day and was found murdered, alongside her support worker six days later.

Oluwatoyin was an activist, with insecure housing, and a repeat victim of sexual assault and harassment, known to the local services and to her church. Aaron Glee Junior has now been charged with her murder. Oluwatoyin’s death has generated important discussions on Black women’s safety and Black men’s role in patriarchy; however, during a time where police usefulness is being debated, Oluwatoyin’s murder also raises important and timely questions around the escalation of abuse and how it risks the safety of victims after reporting violence to the police.

Escalation is simply the worsening of abuse.

This can occur suddenly or gradually and can include abusive behaviour increasing in severity (such as complaining that you use your phone too much progressing to monitoring who you message and call, checking your phone records and installing tracking devices). Alternatively, escalation can characterise the transition from one type of abuse to another; (physical violence to sexual violence for example, or emotional control that gradually incorporates financial control also). Escalation in an abusive relationship is a common tactic used to maintain power and control over a person and is deeply rooted in the insecurities of the perpetrator. A perceived loss of control – if their partner is gaining independence, leaving the relationship or standing up for themselves – is likely to escalate the abuse.

This is reflected in statistics whereby 55% of women killed by their ex-partner or ex-spouse were killed within the first month of separation, and 87% in the first year.

As a domestic abuse survivor, I am a victim of Abuse Escalation.

It took me many years within an on-off relationship to leave my abuser for good. Prior to ending the relationship, my abuser used coercive control, Gaslighting, emotional, financial and sexual abuse to manipulate me into being submissive. Like many, the abuse escalated once I left. Now faced with an unprecedented loss of control, my abuser adapted stalking and harassment techniques to try and maintain a sense of power, and for a while he was successful. I began to accept that I would just never be free of him. The more I ignored his messages or didn’t reciprocate his advances, the more outrageous he became.

He would magically turn up wherever I was, once following me to a different city when I went on a date, sending me evidence of his whereabouts and of proof that he knew mine. Two years later, I still ferociously check the registrations of white vans that drive behind me, terrified that he’s found me again.

I began reporting this to the police, and on every occasion they were painfully slow to react, taking hours to reach his location, giving him a chance to flee the scene. Each time I was told the incident would not be pursued, and I was simply too exhausted to dispute the unjustness of this. Within one dramatic scenario indicative of the situations he would force me into, I received a series of pitiful texts outlining that he had been arrested, with images of his cell as proof, demanding I “bail him out”. I informed the police that someone in their custody was using an un-prohibited phone to harass their ex-girlfriend – now they began taking the abuse seriously. The next day I bounded into the station, armed with a portfolio of evidence to make a statement, naively believing that this would be the end of years of torture.

I asserted I wanted a Non-Molestation Order or Stalking and Harassment Order against him and was told that this would simply not be possible, as a warning had to have been given first – warnings that should have been issued during all the multiple occasions I had reported the abuse in the past. After the warning had been issued, the police rang me and told me that my abuser seemed to “take their warning on board”, and because they “had a good sense of character” he – the person with an extensive violent criminal history who had been in jail less than 24 hours before – seemed like an “alright guy”.

The police simply gave my abuser the heads up. They gave him chance to prepare more insidious methods of abuse; following me on foot after nights out, breaking into my car to take non-valuable items, moving house so that I couldn’t take him to small claims court for the debts he owed me, creating fake social media accounts – things that I knew were him, but could not be proven. After his “warning”, the abuse continued for six months and culminated in me moving to a completely new city to escape him. I continued to compile evidence, but, despite being advised to report any and all unwanted contact, to this day I have not reported him to the police since.

I’d lost my faith in the system and could not face feeling invalidated again.

My experience is not unique and my views on police usefulness are not biased, it is formed from both personal and professional experiences as a Domestic Abuse specialist who supports female and non-binary survivors. I see repeatedly how the system fails to adequately provide justice for domestic abuse victims – in over 6 years of working in the sector I have not supported a single person who has received the retribution they have deserved through the court system.

I am witness to how a person summons the courage to report their abuser, only to not be taken seriously by the police, be unable access free legal aid, or for their evidence to not be deemed sufficient for the CPS to consider it as viable for a court hearing.

Those with racial, gendered and cultural privilege will see more favourable results. For those who do find the strength to persevere throughout a criminal justice system that does not favour the victim; they will be faced character assassinations used by the perpetrator to justify the abuse, whilst the abuse escalates outside the court with little protection. The added risk of re-victimisation by family, friends, colleagues and professionals, broken restraining orders, financial implications, potential child custody negotiations and increased social services involvement create dangerous physical and mental implications for the victim, which I safeguard, risk assess and support.

I have supported clients to advocate for themselves during criminal proceedings, to not feel pressured to submit to negotiations if they did not serve them, only to be faced with new escalating patterns of abuse which occurred immediately after every court date.

Within 24 hours they would be targeted: prank calls, vandalism, harassment of friends and family, anonymous complaints made to their places of work, death threats, surveillance, and even having allegations of child abuse made against them. One abuser remained 31ft away from his victim at all times, following her throughout her day, but always remaining at a legal distance outside of their 30ft restraining order – the police didn’t reprimand him.

Witnessing this as a support worker is depleting.

Reporting to the police is often the only avenue that offers the possibility of official justice and validation, and despite the likelihood of this outcome being minimal, a victim should never be deterred from this. My role is to ensure transparency so a person is informed of their options, the possible outcomes of each and feels empowered to choose the route of support that is suitable for them. To be the facilitator of this empowerment is a monumental responsibility; an element of hope needs to be maintained in order for the victim to be able to persevere each day.

When the abuse escalates, and you see the mental and physical health effects these institutional failings have on an individual, I’m routinely riddled with a sense of guilt and complicity which evolves into burnout, a complete lack of trust in the system and regular existential crisis’s where I question the validity my role within the system – how can we sufficiently help and protect someone within a flawed system that routinely fails victims? This weariness with the system is supported by statistics: 85% of those experiencing domestic abuse sought help from professionals an average of five times before they received effective help, and only 7% of domestic abuse-related crimes reported to the police will end in conviction. As support workers, we are the people holding up those who the system fails.

This issue speaks to many things that require a robust analysis beyond the scope of this article, but I will address briefly here. At the individual level we see how dangerous ‘Fragile Masculinity’ is and how the notion of shame translates to the everyday experiences of victims.

From being called a “slag” after you reject someone in a pub, to Honour Based Violence, a type of abuse which is committed to protect or defend the honour of a person, family and/or community, and in some cultures can result in Honour Killings, the tenacity of an abuser should never be underestimated. The sense of entitlement creates an unwavering audacity that forever will infuriate me. Fundamental flaws in the patriarchal way we socialise our children normalise female subordination and male dominance, that make the inability to accept rejection a death sentence for those most vulnerable.

At the community level, we see how victim-blaming mentalities spouting “why doesn’t she just leave/report him?” are obsolete. A person must first have the capacity to recognise their experiences as abusive, before identifying themselves as a victim worthy of retribution.

For communities from marginal ethnic backgrounds, an established lack of trust in the police presents a barrier to reporting.

For those with insecure immigration status, reporting to the police is often perceived as a threat to their security, often due to their immigration status being used as a tool for abuse. Only 1.2% of cases discussed at MARAC (Multi-Agency Risk Assessment Conferences) noted the high-risk precarity of LGBT+ victims. Not only does a person have to overcome enormous mental, financial and practical barriers before leaving the relationship, but, it is also naïve to assume the abuse stops the moment they walk out the door.

At the societal level, it calls to question the role of police and the criminal justice system in domestic abuse cases. Currently, we are seeing the implementation of the revised Domestic Abuse bill. Whilst problematic for many reasons, the CPS approach is fundamentally problematic because “Domestic Abuse” as an umbrella term for all abuse is not a crime. Whilst a person can be convicted of crimes such as “Coercive Control, FGM, or Grievous Bodily Harm” in relation to patterns of abuse, you cannot be convicted of “Domestic Abuse” per se. This gives abusers a colossal loophole to manipulate, as it makes reporting fundamentally more difficult. Whilst you may have a catalogue of evidence, if that evidence does not prescribe to an alternative type of crime, the CPS will simply reject it.

As #BlackLivesMatter activists chant ‘Defund the Police’ the value of police for the protection of victims of domestic and sexual abuse is often raised. Within a system where domestic abuse prosecutions fell 24% in 2019, and where only 1.7% of reported rapes were prosecuted in 2018/19, arguing that the police are doing an adequate and sufficient job at defending some of the most vulnerable people in society is outdated.

Those arguing that defunding the police would enable resources to be redistributed to the dangerously underfunded community services are advocating for a victim-centred, grass-roots approach to justice. The criminal justice system currently slaps a plaster over a broken bone and sends victims on their way.

Oluwatoyin Salou’s case proves that this approach not only doesn’t work. But, costs far more than we could imagine.

If you have been affected by any of the issues raised in this article, please contact one of the following organisations:

Rape Crisis UK

Supporting victims of sexual assault (UK) 0800 160 1036

National Domestic Abuse Helpline

Supporting victims of domestic violence (UK) 0808 2000 247

SUZY LAMPLUGH TRUST

Supporting victims of stalking (UK) 0808 802 0300