Last week, Michelle Obama received criticism after she stated, “you can’t Tinder your way into a long-term relationship”.

In the UK, 7 million people are registered on dating sites with around 1 in 3 relationships starting online. And many came to the defence of those who have seen successful companionships flourish. The question should no longer be whether romance online is plausible, but how do we ensure these systems are safe for their increasing users?

A 2016 study showed that the number of people reporting that they were raped on their first date with someone they met on a dating app has risen six-fold within five years.

Safia* was sexually assaulted in February, after meeting a man from MuzMatch, a dating site for Muslim communities. She is committed to raising awareness of her experience and preventing harm to more women. She tells Restless; “I started using MuzMatch to take control of my own love life. In South Asian cultures often when a woman reaches the age of 24/25, your families start talking about marriage and family involvement in who you date is common. I’m very independent, with my career, and wanted to have control over who I date, so, I downloaded the app. I knew a few people who had gained successful relationships from it and I wanted that for myself. ”

“This was the first and only time I met someone of the opposite gender on the app. He told me he was a doctor and I thought I’d chosen a safe location; a shopping centre, and I’d initially come with a friend. In hindsight, there’d been red flags in our conversations, but I’m not very street-smart when it comes to dating, so I naively went along with it when he refused to see my friend.”

“During the date, he said it was his birthday, and demanded I buy him a present. He selected gifts that would total nearly £500 and when I tried to leave he shouted and I was so embarrassed I froze and submitted. Later when I tried to escape, he jumped in my car with me and sexually assaulted me, only leaving when my mum tried to ring me.”

Later when I tried to escape, he jumped in my car with me and sexually assaulted me, only leaving when my mum tried to ring me.

“I definitely won’t be using dating sites again, I’ve lost confidence and trust in others, and I’m unsure how I’ll deal with the cultural pressures to date.”

Safiya hasn’t told her family due to the shame attached to women’s sexualities in her culture, noting that her mum would be disappointed; it would be shameful and dishonourable. “My dad has overcome health issues recently, so I don’t want to upset him. Not being able to confide in my family has been difficult as I’ve been dealing with everything myself”.

Despite this, Safiya reported her perpetrator to the police.

“I attended an appointment with a female PC Constable who deterred me from giving a statement.”

“She told me numerous times ‘you need to move on with your life. We’re in a pandemic, there are more important things going on in the world.’ After pleading with her and returning a month later, she eventually agreed to look into it. She found information that he had multiple accounts under different names and was known to the app after being reported by numerous women. She said she thought this information should be sufficient for me to move on, and I found that unacceptable.”

Initially, Safiya thought a female officer would be more supportive emotionally, but this only made her blame herself more. She made a complaint and a male sergeant was assigned to her case. “This sergeant is now also off my case after I overheard him dismissing me to a colleague who accidentally had him on speakerphone. I now have a new officer who seems unoptimistic about being able to identify the man due to the barriers involved with accessing information from dating sites.”

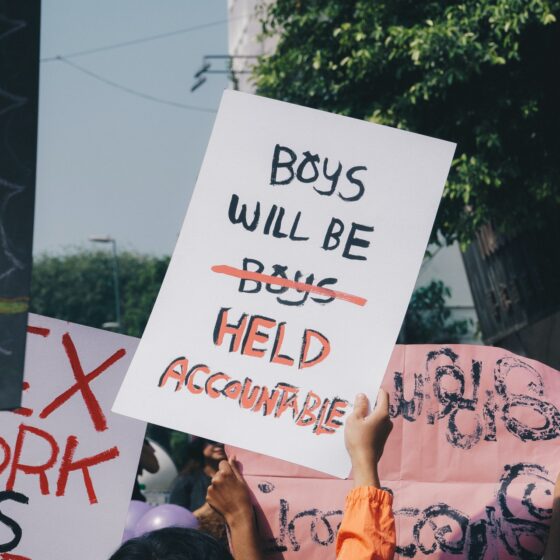

I think if I was a white person – particularly a white woman attacked by a Muslim man – my case would have dealt with quickly.

A person who preys on women made vulnerable by cultural expectations needs to be taken seriously. The police have failed me and I feel like I’ve been going round in circles and have made little progress 8 months later.

Yasmin Aslam, a Senior Project Officer specialising in Domestic Abuse in BAMER communities offers insight into changes that need to occur at the community and institutional levels:

Open dating without family involvement isn’t accepted in our culture, so this can push girls like Safiya to use dating sites secretly. Combined with the pressure to marry by a certain age this makes young women vulnerable. Younger generations are thinking differently and the community’s attitudes to dating needs to adapt to ensure our daughters are safe.

We need an educated police force so that the cultural impacts on a person’s vulnerability and ability to report abuse and assault are understood. There needs to be avenues of obtaining criminal justice that is culturally sensitive and responsive. We need specialist teams solely dedicated to BAMER women, who are not only from the communities, but they can work with the communities whilst challenging institutional bias.

The police need stronger partnerships with dating apps; background checks and the disclosing of sexual criminal offences, regulations that make information sharing easier in cases like this, and stricter policies for serial perpetrators who use fake accounts.

Dating ultimately should be a fun and liberating experience and apps have a responsibility to ensure their users are safe. Being mindful of these risks is important for new and seasoned dating app users alike.

Ways to safeguard yourself can include;

- Verifying a person’s identity before the meeting. Ask probing questions, trust your gut and only meet someone you’re confident is who they say they are.

- Look out for red flags, such as; not having social media or profile pictures, wanting to talk outside of the app or only via calls; having inconsistent or unclear backstories or feeling like you’re being rushed into meeting in person

- Meeting in a public place and familiarising yourself with potential exits, security and help points

- Making use of a code word campaign that was introduced to help women flee unsafe situations whilst on a date. If you’re uncomfortable on a date, ask a member of staff for “Angela”.

- Having emergency contacts on speed dial

- Arranging for a trusted friend or family member to be a direct point of contact throughout the date, with a safety plan, or code words or asking them to meet you afterwards.

- Investing in safety precautions such as rape alarm key rings

- Knowing and enforcing your boundaries throughout the date.

- Set a precedent for what you will and won’t tolerate from a partner and dispute any unwanted interactions.

*Pseudonym used to protect the victim