A beautiful, frail lady lies dying in a Norwegian hospital as her old lover’s letter is read aloud to her. His words are full of empathy, comradeship, gratitude for their time together and promise of continuing love. She smiles as she listens, and dies some hours later. He will die three months later. She is Marianne Ihlen, and her letter and it’s promises are from Leonard Cohen.

The letter brought a sea of collective sighs when it was made public around the same time. Now in his film ‘Marianne and Leonard: Words of Love’, director Nick Broomfield fills in the half-century of history between these two star-crossed seekers, giving us an unforgettable portrait of a romance that inspired two of Cohen’s greatest songs – ‘So Long Marianne’ and ‘Bird on a Wire’ – but, perhaps unwittingly, also raises some complicated questions of sacrifice, inevitably on the woman’s part.

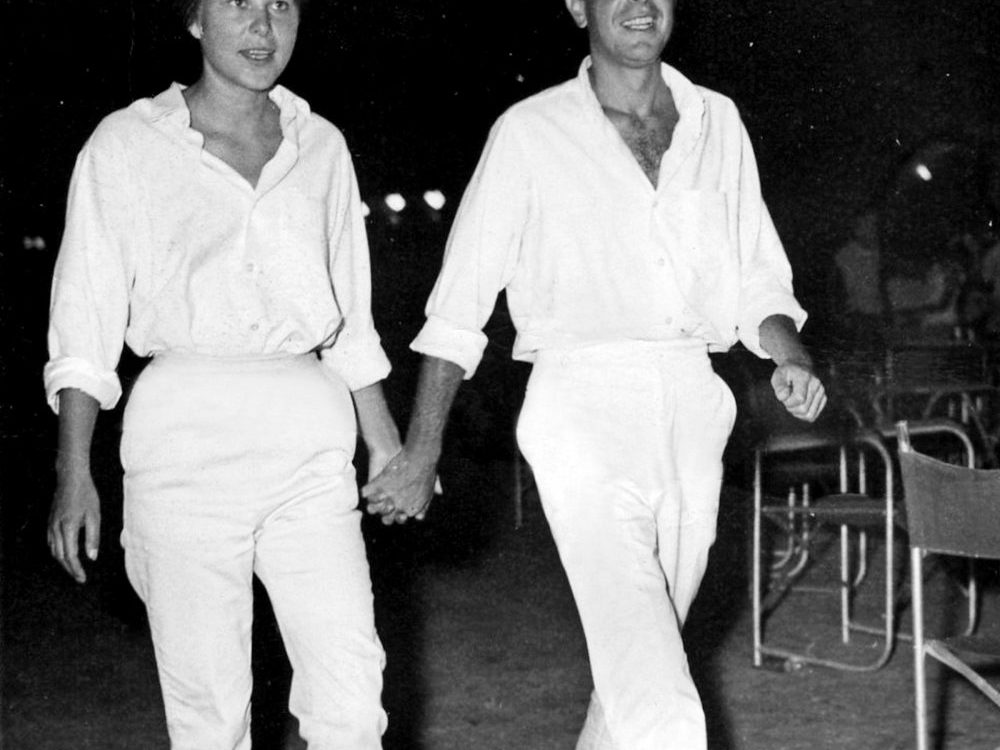

Marianne and Leonard first met on the Greek island of Hydra – an idyllic spot in the Mediterranean, full of bobbing boats, wineglasses that never emptied, sunsets and married couples intent on seeking personal fulfillment of a particular 1960s variety.

After Marianne and Leonard first met in a bakery, they were inseparable and, with the departure of Marianne’s writer husband, soon set up home of apparently idyllic routine, him writing poetry and novels, thinking, posing, her cleaning, shopping and feeding him. The film’s sun-bleached footage from the time shows two people both insecure in their physical appeal, but made beautiful and glamorous by their romance. She says in the film, ‘I was his Greek muse who sat at his feet.’

If it was blissful, it was destined not to last, and this is where the story might become particularly difficult for modern women. If the idea of his woman tending to his every need seems a bit iffy, just wait until the part where he decides he ‘needs to see real life and get inspired’ – aka do a bunk and go back to Montreal, put his first step on the path to musical superstardom, and satisfy the dreams of a thousand female groupies in the process. If Marianne still sat by his feet for half of the year when he returned to Hydra, there was now a growing group of women queuing up to sit on his knee. Leonard explains in the film how he became obsessed with the idea of the ‘sexual expression of friendship.’ One bandmate remembers in the film, ‘He became the poet for the quasi-dissatisfied woman’ – i.e. lethally seductive and allergic to commitment.

Both these chapters in her life presented Marianne with challenges that a young woman today might scoff at. During her time on Hydra, both her romantic partners were talented, creative people, and she was surrounded by similarly aspirational types. As Marianne puts it in the film, ‘I was the only one who didn’t write, paint. Everyone was an artist. I would say, I am an artist. Life is art. I am living. Not very original. Everything is wrong with me. It’s a pity.’

Then later, she joined Leonard in Montreal, but that was when reality truly bit, when she realized that he would never be exclusively hers again, This was epitomized by Leonard’s joyful reworking of his fling with Janis Joplin with the erotic ‘Chelsea Hotel’.

An acquaintance of theirs at that time, Aviva Layton, married to equally errant writer Irving sums it up best when she says, ‘Poets do not make great husbands. You can’t own them. They’re elusive creatures, married to their muse. But a man like that, is a man every woman wants to have.’

The saddest part of the film is Marianne’s own realisation of the futility of her own position. She says, ‘I wanted to put him in a cage, lock him up and swallow the key. He was always sought after by everyone. All the girls were panting for him. It hurt me so much. It destroyed me. I wanted to die.’

Somehow, despite Leonard’s constant escapes to other places and other beds, she remained being his muse, and director Nick Broomfield is more generous with her than she was with herself. Broomfield is a trustworthy source on this aspect of her personality as he too became lifelong friends with Marianne, briefly lovers, after meeting her on Hydra a few years after Leonard first left.

He tells me of how she encouraged his interest in filmmaking and was never the kind of objectified, enigmatic, passive object the word ‘muse’ conjures up.

‘Muse is a passive term, and I don’t think she was particularly. She was very involved in furthering the careers of the men in her life, in a very positive way, including myself, that’s why I feel I can talk about it. She always said, “Believe in yourself, do it, move onto the next phase.” So she was very active. It’s a very vague term, and it doesn’t really refer to the ability Marianne had to really home in on the strengths of people, be receptive enough to encourage them.”

‘She was hard on herself. She’d been involved with these very powerful men, and instead of realizing she had this incredible strength which was to further the strength of others, she felt she needed to have a talent of her own, as an artist, which she didn’t. In a way she had what a great record producer might have, the ability to listen to someone’s work and say, “What you should be doing more is this…” but she didn’t see herself like that. She didn’t have the ego to match the generosity.’

What about Leonard’s increasingly casual treatment of Marianne, culminating in his creating a second family unit in Montreal, with a woman who helpfully re-named herself Suzanne? Another poignant part of the film is when Marianne describes opening her front door in Hydra to discover Suzanne standing there with a young son, ‘wondering when I was moving out so she could move in’.

It seems Nick Broomfield is equally philosophical about this course of events, at least for Leonard. He points out that Leonard continued to send money to Marianne and her son Axel, long after the two eventually parted for good, and she decided to make her way back to Norway where she found a conventional job, got married and settled down into the normal life her mother had always wanted for her.

If it was such a life-defining love affair, why did Leonard leave? ‘I had to escape,’ he says in the film. ‘It was a selfish thing, but didn’t seem so at the time. It seemed a matter of survival.’ Sound familiar ladies?

Broomfield is more forgiving. ‘Leonard gave what he could give, he couldn’t give any more. I think people are very different in their ability to… a lot of his work is about his inability to commit, it’s just who he was.’

Isn’t that letting him off the hook? Broomfield thinks not.

‘Don’t you think we’ve all had love affairs that haven’t necessarily fully flowered, but remained enduring? Affairs are very different, some are tortured, some go somewhere, some are patchy. We grow up with this chocolate box version of ever-after love which very rarely, almost never, exists. That level of commitment is difficult for a very long time, it requires understanding, patience and compromise – all rather unattractive words.’

Spoken like a true artist, I suppose. In the final reckoning, we can’t take Marianne’s agency away from her, and certainly Leonard never tried to. Ultimately, if she was able to forgive him for his behavior through the different phases of their relationship, then I should too. And that she did is clear from the film – including footage of her in the front row of one of his concerts in Oslo, singing along with the words to ‘So Long Marianne’ with a beaming smile on her face, many years after they parted, to the impossibly moving ending when she dies so soon after hearing his final message. As a friend of hers in the film reflects, ‘It was a love story of 50 chapters. She had a compartment of her heart that was always married to Leonard.’

There may be elements of all this that inspire more than a few twinges of dissatisfaction for women today, but it does make for a great love story.

MARIANNE & LEONARD: WORDS OF LOVE will be released in UK cinemas on July 26th

Featured image is the copyright of Babis Mores