China’s history of censorship is certainly no secret – the country is known the world over for keeping tabs on its citizens, censoring online content, and blocking certain sites on the internet – a phenomenon known as the great firewall of China.

These policies have had tangible impacts on social movements throughout China’s 70-year-long history. But even before the People’s Republic was founded, the effects of censorship could be seen through the oppression of China’s women.

What do a lost language and a social movement have in common? Nüshu – literally meaning ‘women’s language’ – was a script created in rural China, exclusively used by women.

The Chinese #MeToo movement may not bear any similarities to the lost language of Nüshu, at least at first glance. But both of these phenomena have a lot to tell us about China’s policies of censorship – and how social movements and communication change as a result.

Similar to many places in the world, women in China were not granted an education and spent most of their lives indoors. Restricting women’s thought through low-literacy rates is not a China-specific problem – but in China alone did this lead to the world’s only women-specific script: Nüshu.

The origins of Nüshu are unclear. An old legend, local to Hunan province, says Nüshu was created by an Imperial Concubine in the 11th century, who used the script to communicate her distress about her situation to the women back home. The most popular theory is that Nüshu was created in retaliation to the exclusion of women from education.

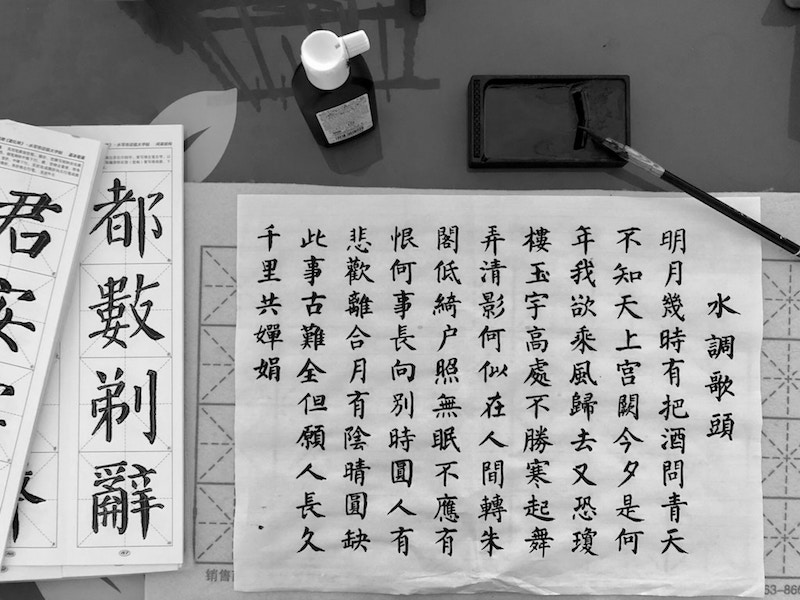

While Mandarin consists of ideograms – each character conveys a different meaning and not a sound – Nüshu was homophonic. Each character represented a sound and together the characters produced the sounds of the local dialect, Tuhua.

Many modern accounts of Nüshu paint the language as the method of communication of the activists of the time. There’s not much evidence to support this – it seems, from most examples of the language, that Nüshu was used to communicate to other women in letters. In China, at the time, there was a tradition of ‘sworn sisters’ – women, related not by biology, but by friendship. This arrangement was similar to marriage and was often facilitated by match-makers. However, when women married, they were often required to move long distances away from family and their sworn sisters. Without the ability to write, they were completely isolated – often not even allowed outdoors.

The most common use of Nüshu was in letters and poems – almost exclusively lamenting their marriages and current personal situations.

It was created for women, by women, and used to communicate their pain and sorrow at an existence in a world, created for and powered by men.

Communication is also central to the #MeToo movement – it may even be the single most revolutionary thing about it. Suddenly, within a few tweets, women had the power and language to discuss things that are often too painful to put into words. Things that were silent and unspoken were suddenly known in a few words: the power of shared experience and understanding quite literally changed the world. A sense of community was created by two small words: I understand you, I’ve been through the same. I’m with you. Me too.

There was suddenly no longer a need to invoke trauma or to justify. The movement created a drastically needed space for survivors to hear and to be heard.

But what happens when this space becomes censored and restricted?

As #MeToo was a global movement, it’s no surprise that it took China by storm. To date, more than twenty liberal intellectuals, media personalities, and activists currently stand accused. While this is less than a tenth of the number accused in the US – in the world’s most populous country, no less – this is not surprising, considering China’s censorship of the movement.

Twitter – the social media platform that was largely responsible for the growth of #MeToo – is blocked behind China’s firewall. However, activists accessed the site and contributed to the movement using Virtual Private Network software to bypass the firewall.

The government soon caught on to the hashtag and shut down the movement. In response, activists changed the hashtag – now a rice bowl emoji, followed by a bunny emoji. In Mandarin, rice is ‘mi’, and a rabbit, ‘tu’ – an ingenious way to avoid censorship.

Screenshots of survivor’s testimonies were shared upside-down to evade the detection of censors – some were even permanently encrypted into blockchain servers, like BitCoin, meaning they were permanently stored on the internet, for those who knew where to look.

So, what does a language and a social movement have in common? Of course, there are multiple superficial similarities – both Nüshu and MiTu relied on homophonic representations of language to evade detection. Both phenomena were mainly populated by China’s intellectual class. Both involved women scorned at the censorship and repression they faced – and still face.

At their core, they share the same essential goal. Communication. Finding a common, shared experience. There is nothing more powerful than truly understanding – and there is no more powerful feeling than that of being truly understood. In the same way that Nüshu allowed women to communicate and empathise about each other’s shared experiences of married life, #MeToo allowed women to share their experiences of sexual assault and misconduct in a world where it is only too common.

Communication was essential to both of these movements – both in the content and the delivery of each of their messages. And, in both these movements, communication flourished, despite multiple attempts to stifle these voices.

In 2019, there are no original speakers of Nüshu left alive. While the script was passed down from mother to daughter, the practice of teaching the script fell into obscurity after women were granted more social freedoms in the 1950s. Now, it is only academics and intellectuals who learn the script.

This is one aspect of Nüshu that the #MeToo movement does not share. While the education of women in China made Nüshu obsolete, the #MeToo movement has as much cultural relevance today as it did when it sprang into the spotlight in 2017.

Perhaps, one day, there will no longer be a use for #MeToo. The very purpose of activism is to change the world so much that the movement is no longer of use. Maybe, one day, historians will study #MeToo and the censorship Chinese activists faced with the same curiosity with which they study Nüshu.

Some ideas are simply too powerful for censorship to be effective. And we can only hope that China’s activists continue to fight for a world in which #MeToo will no longer be necessary.