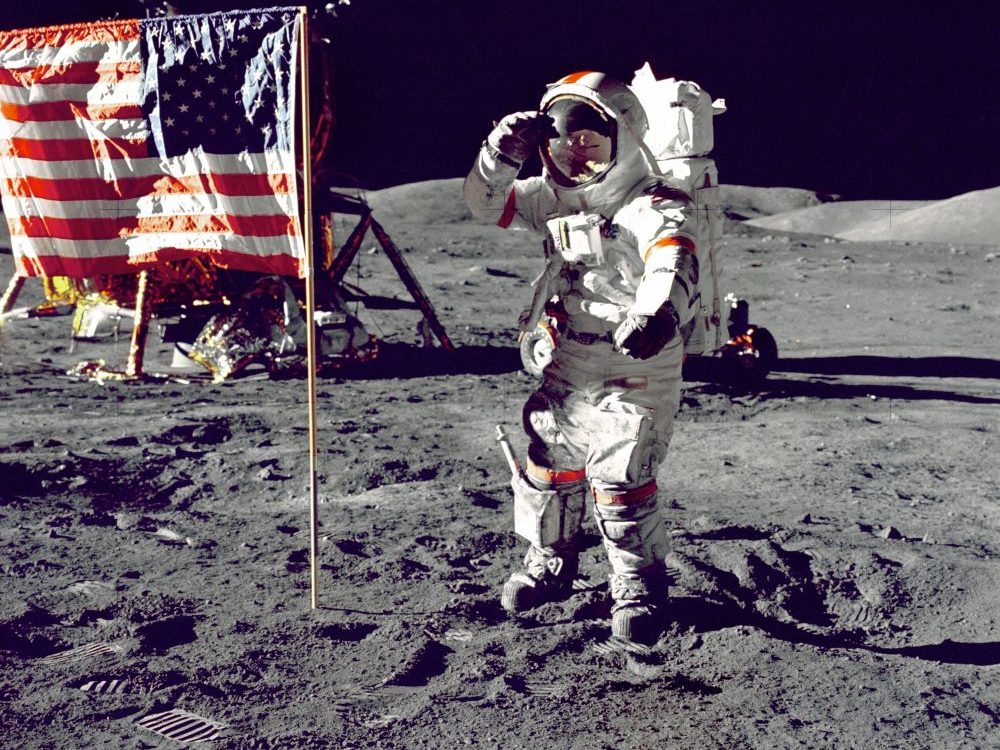

Never mind the political chaos currently being waged in every quarter, the 50th anniversary of the first moon landing is a unique date that unites all of mankind, the half-century of our greatest exploit, when we stopped bickering long enough to land on the moon.

The Apollo program demonstrated human courage, mechanical know-how and team spirit that have never been matched. For one group of women, however, it also presented as many personal challenges as it did privileges, and their memories of those heady days remain bittersweet, detailed in a documentary that was shown again on PBS this weekend.

The lives of the Apollo Wives could be divided into three distinct chapters. From the early 1960s, they began family life as the partners of pilots, hardworking military men dedicated in equal measure to home and country.

If these men were reliable and routine-filled, they were also the best in the world at what they did, with their addiction to danger only adding to their appeal. Apollo 17 pilot Eugene Cernan’s wife Barbara remembers him describing himself once as “195 pounds of speed, dynamite and deception”.

Their wives were in awe of their bravery and derring-do, but they had always planned to marry engineers, not astronauts. That all changed in 1962 when President John F Kennedy announced his desire for Americans to conquer the new frontier, win the space race with Russia and send a man to the moon by the end of the decade. The Apollo program was born.

For the chosen few, it meant travelling further than ever before, and exhibiting displays of unprecedented courage and know-how. For

Janet Armstrong and her fellow wives, it meant another challenge of adapting to life in Houston. Before her death last year, she remembered how it “was just assumed at that time that the wife went along and did what the husband wanted. I think times have changed.”

What they hadn’t prepared for, though, was the constant absences from home by the dedicated Apollo astronauts. Rushed conversations went along the lines of, “Where are you going?” ”I can’t tell you,” before husbands disappeared, sometimes for months at a time.

With the men tucked away from millions of public, curious eyes, their wives instead became the object of intense attention, as the press constantly descended on their homes for each journey into space. There was no guarding against such scrutiny. “I told the press they could do whatever they wanted, as long as they didn’t interfere with my friends and family watching the TV. Well, they loved that,” remembers one.

When the astronauts did come home, they were exhausted, often asleep, at other times withdrawn through years of training and prep. The wives, however, were expected to remain on their best behaviour, well-dressed, religiously conventional and domestic goddesses to boot.

If the wives had been scared for their husbands’ safety before, now they were terrified, and the risks of the mission were brought home all too sharply with the tragedy of Apollo 1 in 1967. A month before the planned launch, the lunar capsule caught fire, killing three of Nasa’s finest men – Gus Grissom, Ed White and rookie astronaut Roger Chaffee. Chaffee’s widow Martha later described the awful day when she received no official word, but feared the worst as, one by one, all the other wives turned up at her door. It was Nasa’s policy to phone other wives instead so they could extend their support to the unknowing widow, until an official finally appeared to break the awful news. Those long hours of pretending everything was okay must have been excruciating for everyone involved.

It was two years before missions to space were allowed to continue, and the danger never went away. The perils of the program and the risk of danger to all the astronauts meant their wives became an obvious focus each time their men’s rockets lifted off. Later, when the world heard those ominous words from Apollo 13, “Houston, we have a problem” in 1970 after the mission’s oxygen tank exploded and left the crew stranded in space, the press descended on their homes once again, for what was dubbed “death watch” for the families watching and waiting. After the crew finally returned safely to earth, the wives’ each repeated what had become their parrot-like public response, “I’m thrilled, proud and happy.”

The press asked, “Why are those wives so calm and serene?” but Apollo 17 crewman Ron Evans’s wife Jan explained, “We had to be. We looked like Stepford wives, but we weren’t.”

The first moon landing caught even the wives by surprise. Janet Armstrong remembered, “We didn’t know they were going to land on the moon until they did. It just all worked, it was amazing.”

There were perks as well as problems. Everybody in Houston and beyond saw it as a point of honor to have an astronaut or two as a dinner guest. Their wives became used to cleaning home, raising kids by themselves, and then powdering up for posh lunches and making the small talk of celebrity by association. However, it soon became clear they had additional personal trials to contend with.

If their husbands had left home as engineers and pilots, they returned as astronauts and superstars. And with superstardom came groupies, even for the ones with, as one wife wryly described it, “two heads”. Many of these men charged with leading our crusade beyond orbit proved susceptible to the temptations of unexpected attention and flattery. As Barbara Cernan once explained, “The odds were not in our favour.”

Apollo 7 pilot Donn Eisele became the first astronaut to announce his divorce, following his involvement with a woman in Florida. For his wife Harriet, the coverage on “every television, every magazine” was humiliating, but she soon found she wasn’t alone. Of the 10 Apollo wives featured in PBS’s reunion film made in 2010, seven had been divorced.

This upheaval led to the most uncertain chapter in these women’s stories, learning to carve their own way after years of living in the shadow of their spouses and having to uphold the burden of societal expectations. But over the decades, they’ve had one thing to bolster them – their mutual friendship, support and understanding, carved by sharing a unique place in history. Despite being spread out across America and beyond, every few years they get together, with the 40th anniversary rendezvous being filmed for an intimate documentary being shown again on PBS this weekend.

Most have now made peace with the challenges of that extraordinary time. Janet Armstrong, who divorced Neil Armstrong in 1994, spoke for many of them when she reflected, “Life goes on, you move forward, you don’t think about the past.”

Apollo may have brought these women unique personal upheaval, fear, scrutiny and trauma, but it has also brought them a unique bond, and it’s clear as they share their memories, they never really got the credit they deserved, for helping the entire program run smoothly and happily, despite the huge challenges they faced.

Except perhaps from one man. Clare Whitfield was previously married to Apollo 9 pilot Rusty Schweickart. She remembers a conversation she once had with American icon John Glenn at a time when she felt the world’s attention was on her husband and his fellow pioneers, and the wives were left in the shadows. It was her country’s first man in space who put her right, referring to his own wife in the process: “You’re wrong Clare. I couldn’t make this flight if it weren’t for Annie. She is my support. You are very important.”

Want to learn more about these unsung heroes? Watch ‘Apollo Wives’ from PBS America