Content warning: This article speaks openly about #MeToo-related topics, such as consent, rape, and assault.

While idly scrolling through Twitter, I came across several heated exchanges about the nature of consent. It’s not the first time I’ve seen conversations on this topic, but these debates had finally managed to cement a thought that had been lingering in my mind since my devastating first break-up:

Can we issue consent if information that would likely cause us to revoke it is purposefully withheld?

These particular conversations struck a chord with me. As an undergraduate, I entered into my first relationship with a man who—unbeknownst to me—was guilty of sexually, physically, and psychologically abusing other women. The university formally found him guilty of this, and, once we broke up, it was something he’d begun to admit to others. He attempted a feigned apology to me, but he and his family saw no issue in how I had spent the best part of two years willingly being deceived by a rapist—at least not enough to do something substantial enough to atone for the hurt caused to me and the countless other victims.

Perhaps the most devastating part of it all was the solace I’d initially found with him in the beginning of our relationship. I had been raped only a few months before we got together, a fact he was well aware of, but chose to lie to me anyway. It was only after our break up that I became inundated with accounts from other women of how he’d abused them, eerily reminiscent of my experiences. I found this harder to cope with than my experience of sexual assault itself.

Jessica, a 28-year-old writer, experienced a form of consent betrayal when her ex-partner spent an evening being intimate with her only to break up with her the following day, something he had known he would do. “I remember feeling so deceived,” Jessica said. “It felt like I’d had my consent violated because I would never have been close to him physically if I’d known where his head was at. But I also felt like I couldn’t feel that way because it wasn’t a sexual assault.”

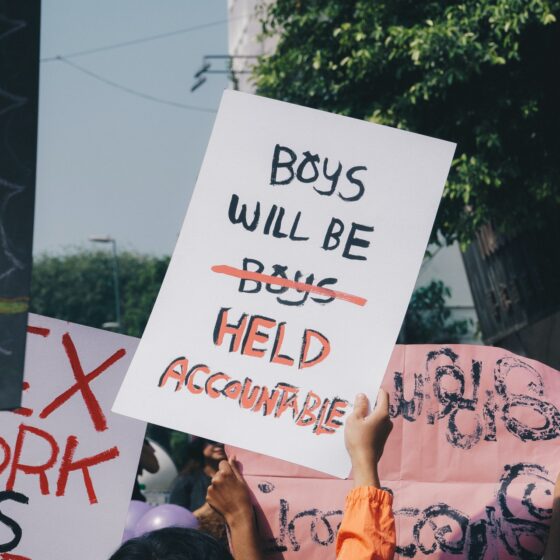

A common theme with women who have experienced instances where their consent was violated or ignored without experiencing ‘assault’ is that their experience becomes invalidated, but it doesn’t.

Innovative writer and actress behind the provocative series I May Destroy You Michaela Coel has gone on to coin the term “theft of consent”. One of the show’s most enduring provocations was to explore the ‘grey areas’ of consent and the extent to which people lie to obtain consent.

“I call it ‘a theft of consent’ because details are purposely hidden from you so that you consent,” Cole says. “If [a prospective sexual partner] had the full details of what they were experiencing, would they give consent?”

In a lot of cases, the answer would be ‘no’.

As it currently stands, instances of consent theft are exceptionally hard to prosecute. Serial rapist Jason Lawrence revealed to one victim, who had initially consented to have sex with him without a condom, that he had lied about having a vasectomy via a text that read: “I have a confession. I’m still fertile. Sorry.” While despicable, instances where truths are omitted to obtain consent occupy territory that is firmly unethical, yet likely legal. In the eyes of the law, it is legal to lie and omit information about your relationship status, age, profession, and even histories of abuse and domestic violence to obtain consent.

Dr. Kyle Murray of Durham University Law School has been researching sexual consent and issues of mistake and deception.

“The value is that it puts sexual autonomy at the front of these offenses,” Kyle said. “Sexual autonomy is the right to make decisions about your own sexual conduct and what happens with your own body. To respect someone’s sexual autonomy, you should put that person’s own choices at the center of the law on consent. If that’s violated, then so is their consent. It’s no one else’s place to say what should be relevant to their own choices.”

Kyle explains that the courts are currently hesitant to broaden the restrictions on which forms of deception are valid. “They’re concerned about the need to draw lines somewhere—risks of over-criminalization, fair labeling—so, it would be difficult to see things changing soon.”

I spoke with several folks who had experienced consent theft, but didn’t know there was a word for it.

“I don’t think it was sexual assault because I wasn’t physically hurt, but I was deceived into an uncomfortable situation,” said Jack, a 23-year-old consultant from Southampton. “The experience was emasculating, and I couldn’t talk to other men about it for fear of having others joking about me being lucky for having a girl force themselves on me.”

Nina, a 22-year-old student from Coventry, UK, describes an instance where she was unknowingly the other woman in one of her earliest sexual experiences. “I was 17 while he was in his second year of college. I was super easily manipulated and impressionable because of this power dynamic,” she said. “It all came to a head one day when he told me he had a girlfriend who he had been dating at the same time as me. He only revealed this once they became ‘official’, but if I was aware of the extent of their relationship, I wouldn’t have done any of it.”

Consent is simple: you either have it or you don’t. But withholding information in an effort to have your way, even when it’s at the detriment of another individual, is abuse and manipulation. And it’s the theft of a human’s right to say no.

The solution to the problem of consent theft doesn’t have to be complex. It simply involves being more honest and open about the nature of our sexual encounters, as awkward and challenging as that may be. And although it may be embarrassing to declare upfront to your prospective sexual partner that they are, in fact, one of many and you don’t intend on seeing them again, at least their consent will be issued based on truth rather than lies and deception.