Ever since I first read Slouching Towards Bethlehem when I was a journalism student I have carried around a battered copy with me wherever I go – folding over the yellowing page corners when something really resonates or a sentence sings, which is often. On a 10-hour coach trip to Berlin, rush hour on the Central Line, in a plane nervously awaiting take off; Joan Didion’s face (complete with those sunglasses) stares out from the front cover at the bottom of my rucksack. My trusty companion wherever I am. Her words a soothing balm to my anxieties.

Didion – literary legend, chronicler of modern American, pioneer of New Journalism, and my ultimate girl crush – turns 85 today. So think of this as a celebration of her work (which spans fiction, memoir, political reportage, screenplays, and critical essays) and what we can learn from it.

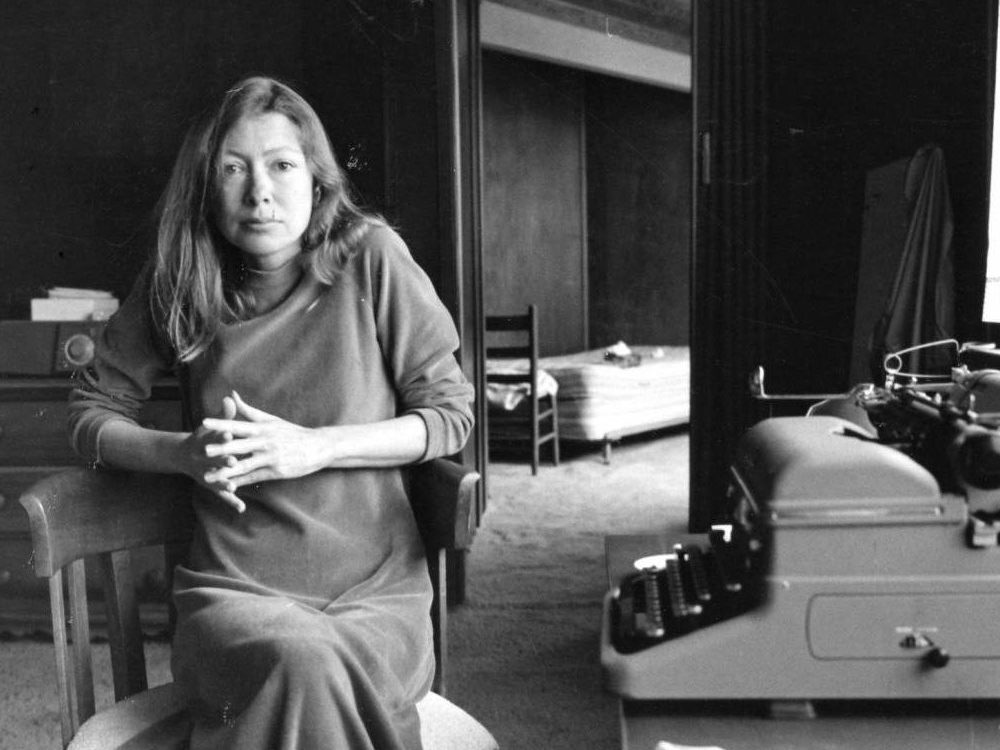

Many have long been fascinated with Didion – not just with her writing but with her whole persona. She gives the impression of being this cool, aloof woman – an outsider observing from the sidelines, casting her sharp eye over everyone – but underneath the steely veneer is a vulnerability which she reveals bit by bit through her writing. The queen of not giving too much away; an enigma within an enigma who oozes style both on and off the page. You can just imagine her tapping on her typewriter, crafting magical prose while drawing on a cigarette, the doors of her Malibu home thrown open so she can hear the distant crashing waves of the Pacific.

Her writing – particularly her mélange of essays – has not only taught me about the multifaceted, messy world we live in, and the wide variety of people in it – from the hippies of San Francisco, Charles Manson and his “girls”, to the Central Park Five, civil war in El Salvador, and the artist Georgia O’Keeffe – she’s taught me about myself. Without wanting to sound too pretentious, Didion has taught me (and still teaches me) how to see, listen, feel, live.

It usually hits you when she’s describing something mundane – and then there it is: a turn of phrase that feels like it’s been written especially for you at that precise moment in time. A shard of gold you just want to turn over in your palm and examine, hold up to the light, and revel in its glory. For me, it was a line in her essay On Self-Respect which she wrote for Vogue in 1961. The essay is all about her failure to get elected to Phi Beta Kappa, an honourary society of undergraduates whose members are elected on the basis of high academic achievement. She writes:

“I lost the conviction that lights would always turn green for me, the pleasant certainty that those rather passive virtues which had won me approval as a child automatically guaranteed me not only Phi Beta Kappa keys but happiness, honor, and the love of a good man; lost a certain touching faith in the totem power of good manners, clean hair, and proven competence on the Stanford-Binet scale.”

The essay is about the disappointment that comes from failing to live up to your own expectations, but it is also about coming to terms with that, understanding your abilities, your worth, and how that informs your sense of self. She writes that people with self-respect have the courage of their mistakes. “Character – the willingness to accept responsibility for one’s own life – is the source from which self-respect springs.”

I read (and reread) this essay during a time when I was experiencing a lot of rejection – a time when it certainly felt like the lights were permanently stuck on red and would never turn green. Fresh out of university, I naively thought I’d walk straight into a job. And when I didn’t get so much as an interview, I felt like a failure. Everyone says you shouldn’t take rejection personally, but at the time it feels like a punch in the gut – it knocks the wind out of you and you wonder how you’ll pick yourself up and throw yourself back into the ring. It makes you question whether you’re good enough. This essay flooded me with hope. I don’t know exactly why. Maybe because it made me feel less alone, or maybe it helped me to see that failure is part and parcel of life (it never runs according to plan) – and to really progress you have to learn from those bumps in the road.

One thing you can always rely on: Didion doesn’t sugarcoat anything. She writes with honesty about her life, her insecurities, her guilt, her what ifs, and sometimes even her stupidity, her carelessness. And yet, these aren’t your typical confessional essays – there is a lack of self-indulgence – she is simply telling it how it is and in doing this she reveals something about you and me and the fallibility of all humans.

Failure is a recurring theme in her work, which seems ironic given how successful she is. But then failure comes in many shapes and sizes. Blue Nights is a haunting book about the loss of her only daughter, Quintana Roo, who died aged 39 – a year and a half after Didion’s husband died. Grief is something she is all too familiar with, and she explores its dark depths with an honesty and rawness that had me fighting back tears. The book delves into this period of mourning, which she likens to the long twilight hours approaching and following the summer solstice; “…houses shuttering, gardens darkening, grass-lined rivers slipping through the shadows. During the blue nights you think the end of the day will never come.” She describes these nights as the opposite of the dying of the brightness, but also its warning.

The book isn’t just about grief, it is also about the power of memory and her reflections on motherhood – overwhelmingly you sense she blames herself for her daughter’s premature death. Didion repeatedly questions her parenting style, and admits that maybe she didn’t bring up her daughter in the ‘right’ way (Quintana seems to have spent a lot of her childhood at Hollywood parties or in foreign hotel rooms). Blue Nights is a poetic elegy to her daughter, but it is also full of fear; fear that she failed at being a mother, fear of her increasing frailty, fear of becoming invisible, and fear that she will lose her ability to write. “What if I can never again locate the words that work?” she asks near the end – every writer’s worst nightmare. But it is also as if she is mourning her loss of self. Who is she now that she’s lost the two most important people in her life? You can feel the encroaching darkness in her fragmented story-telling. This book will speak to anyone who has lost a loved one and suddenly realised the fleetingness of it all.

“Life changes fast. Life changes in an instant. You sit down to dinner and life as you know it ends.”

This line is from The Year of Magical Thinking, her best-selling book which untangles the aftermath of the death of her husband, John Gregory Dunne. He had a heart attack at the dinner table the night before New Year’s Eve. She writes that she kept his shoes just in case he returned; it is the year she spent wishing for something that could never happen. The impossible. Haven’t we all yearned for something like that? Writing about grief, helped Didion to grieve. She was attempting to piece back together her shattered life, but she was also clinging on to her husband. In an interview with The Paris Review she says she didn’t want to finish the book, because finishing it meant letting go of him. You can tell. She prolongs the ending; eking out the memories of John alive, so she doesn’t have to confront the reality of life without him. It is a heart-rending yet restrained memoir which grabs you by the shoulders and shakes you, urging you not to take anything for granted.

This piece has taken a rather melancholy turn. I can assure you that Didion doesn’t just write about death and failure (see Goodbye to All That, one of my favourite essays) – but she does have a knack for putting into words the feelings most of us find difficult to articulate.

Let’s end on a positive note. “We tell ourselves stories in order to live,” begins The White Album. It is one of her most famous lines, which has been thrown about so much it has almost become a cliché. Almost. I still love it. It is a reminder that life is complex; we need stories to make sense of it all. And Didion does just that.

Photo credit: Jill Krementz