Around this time last year I attended an International Women’s Day event hosted by a domestic abuse survivor. She gave a reading from the book she had written about her experiences of an abusive relationship, a whistle stop introduction to the effects of abuse on survivors, and offered a Q&A at the end. Unfortunately, I left the two hour session feeling frustrated. Not because her story as a survivor of abuse was invalid – all experiences of abuse must be believed – but because her experience of accessing support, and the advice she offered to the room, was entrenched in her privilege as a white woman. More specifically, her white privilege had given her unwavering faith in the police. This privilege became apparent when she told a Muslim woman who asked how she could navigate the complex intersections of abuse, family and culture: “I couldn’t recommend going to the police enough”.

This is a particular form of white privilege that manifests itself as white feminism, through the ways in which survivors of domestic abuse, rape, sexual assault and sexual harassment often perceive the police and more broadly, the state, to be a source of protection and an upholder of justice. As a domestic abuse specialist supporting ‘BAMER’ and LGBT+ survivors, this white feminism is something I see as an endemic symptom of the Violence against Women and Girls sector and it’s something we saw on display as events unfolded over the past week.

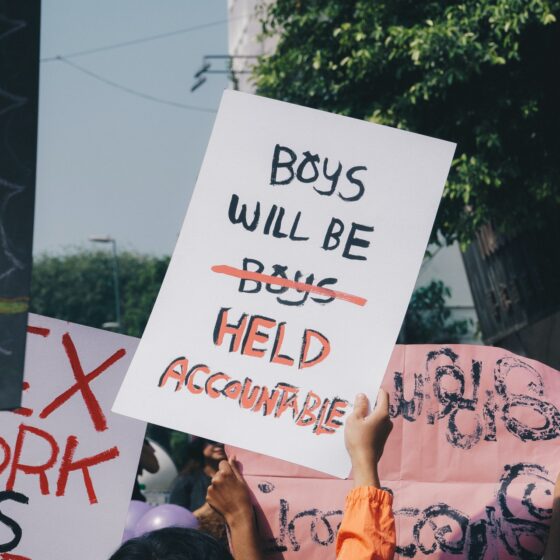

Unsurprisingly, yet no less infuriatingly, it took a white woman’s tragic death to ignite widespread outrage and a call to action against male violence. Not the disappearance and death of Blessing Olusegun; or the murder of Nicole Smallman and Bibaa Henry, and the fact police took pictures of their bodies; but the death of Sarah Everard, a white victim. It then took the overt violence of the Metropolitan Police against vigil attendees who were peacefully protesting Sarah’s death for police brutality, institutional violence and a culture of misogyny to be taken seriously. Not the fact that there have been 415 reports of sexual abuse by police officers within the last two years, or the ways that the police officers who perpetrate domestic abuse are protected by the system, but the use of extreme force against white female protestors at a vigil. This evidence has been plain to see this entire time, but so many people chose not to see it. Instead claiming that police brutality doesn’t exist here. Conversely, many women did see it, but chose not to care or didn’t feel compelled to mobilize.

These past two weeks, for the first time you could see the veil fall from people’s eyes as twitter documented the nationwide disgust in real time. The cogs were finally starting to whirr as people questioned whether or not the police are actually the useful protectors they’d always believed them to be, or whether maybe, the Black women who they’d admonished for ‘going too far’ for chanting ‘ACAB’ during BLM marches, had a point after all. Through a lens of whiteness, white, cisgender women have been able to hold faith that the police will protect and serve them, as they’ve never been in a position to be proven otherwise. For many of the activists of color who watched this lightbulb moment unfold, we saw those who had been socialized to never question the status quo, who had taken for granted that our current systems could be the only framework, start to fall apart.

Take something as simple as contacting the police for example. For many white women, you will have undoubtedly been taught to ring 999 in an emergency and that, when you do, the police will arrive to help. You probably have faith that they will arrive swiftly, that they’ll listen to you, center your feelings and your experiences. By the time they’ve left, they’ll have offered solutions to your problem, leaving you feeling safe and secure in the knowledge that justice will be served. If you’re contacting the police as a white survivor, there is a higher likelihood for you to expect to be heard, believed, safeguarded, and your perpetrator be punished. If this doesn’t happen, you may take this as a flaw in a system that you still believe is fit for purpose. While many women have had to consider whether the system is inherently against you as a woman, you’ve probably not also considered what it’s like for those of us who are of color and women. Doubly worse, if not more so.

For many survivors, picking up that phone to call the police requires immense contemplation, a weighing of pros and cons, and an evaluation of immediate and long-term risk, because we know that a positive outcome isn’t certain. Black women may be seen as too strong to be victims; a lesbian‘s experience may be seen as less serious, or she may be perceived as equally at fault as her perpetrator; a trans woman may have their identity questioned before they have their experience believed; a disabled survivor’s abuser may be seen as a carer; a neurodivergent victim may be gaslighted; a woman with insecure immigration status will have their immigration data passed to the home office, with the threat of detention and deportation; or a Muslim woman may be subjected to PREVENT protocols. As a domestic abuse practitioner supporting and advocating for ‘BAMER’ and LGBT+ survivors, I have seen all of those examples translate into the violent revictimization of survivors at the hands of the police, and services who are designed to support them.

So for me and many like me, the images we saw of the violence at Sarah’s vigil didn’t represent a lightbulb moment of new information suddenly becoming clear, it brought forth a tsunami of hopelessness and disillusionment. When white, cisgender, non-disabled women are no longer protected from the police, what hope is there for the rest of us?

For me, the hope lies in grassroots community organizations that have been mobilizing for years and continue to do so. Rather than working with the institutions that harm us, trying to rehabilitate the state by giving more power to the police that will only be used against marginalized communities, instead of advocating for carceral solutions that prioritize punishment and state powers, naively thinking we can be supported and protected without bias, we need you to stand with us. We need white women to use the privilege that has protected them for so long, and direct it towards the protection of others. Use that privilege to advocate for the even distribution of resources and funding, so that community reparation projects that value prevention and community rebuilding can have the same momentum to fight violence against women and girls as mainstream organisations. We want you to listen, unlearn, re-learn and question what you thought were unquestionable facts about society.