This article contains triggering content.

It’s always the same story. The same shaken voice. The same conversation on the phone to another friend who has experienced sexual assault. The same response from your male friends when you tell them every woman you know has a story about being sexually violated while he informs you that his friends are not like that. It’s never his mates, never his boys. Even in his workplace, at the Christmas parties, he hasn’t witnessed anything inappropriate. He was raised by a strong mother, surrounded by women, so he can’t even imagine what goes on in the mind of a man, who could mistreat a woman like that.

And there lies the issue. So many men don’t know anyone who has or would sexually assault a woman while most women know another woman with a story. Or have their own story. Rape Crisis reports that 20% of women (that’s one in every four) are raped while 4% of men are raped in the UK. According to Rainn, every 73 seconds, an American is sexually assaulted while UN Women share that 35% of women are raped worldwide (with lower statistics than expected due to the number of rape cases which go unreported. The number of unreported rape cases in some countries, is as high as 91.6%).

As Salma El-Wardany pens in her latest poem about the chasm between men and women’s proximity to sexual assault, “those numbers don’t add up”. If women are most likely to be assaulted by those they know, those who are around their male friends, brothers, colleagues, lovers, partners, husbands, then surely their male peers know of them and are around predatory behaviour too.

“I don’t think men even know what rape culture is or looks like,” says teacher Nayema Jilani, 34, based in the West Midlands. “They don’t know that that time they grabbed a girl in the club, that was predatory behaviour. The time they let it slide between their friends, they were a part of the problem. It comes from a lack of consensual education and then women having to brush it off as the ‘norm’. Whereas if men were called out by their friends, some wouldn’t do it again.”

From her personal and professional life, Francesca, a 23-year-old Londoner, who works in sexual education, has learned that many of us have learnt of consent only in degrees of extremes. “People conceptualise rape as violent or by a stranger when actually it is more likely happening in ‘grey’ areas with close friends or partners.

“Non-consensual sex is rape, and men’s sexual dominance and prowess have been seen as an explanation of like ‘ah I did it because they really wanted’ to or because they ‘had’ to have sex.”

There’s also this mistaken idea that if you’re not drugging, raping and grabbing women by their pussies then you’re exempt from sexual assault or rape culture. It’s why gaslighting victims of sexual assault, especially by abusers who are unaware of their actions, is so common. Abusers, whether their predatory behaviour is unbeknownst to themselves as attacks or their friends, view exerting their strength as a cog in their masculinity.

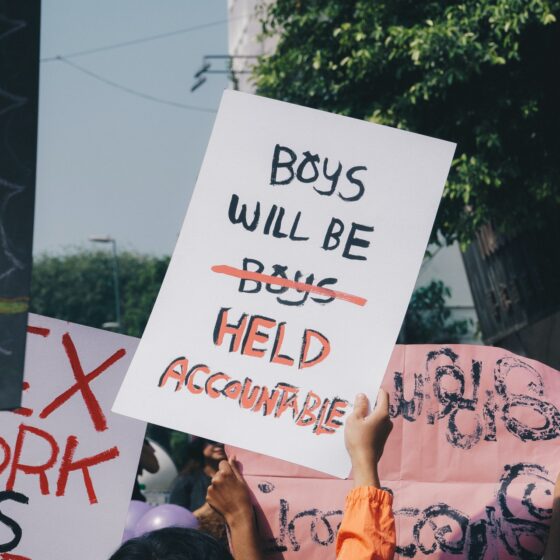

It’s why 19-year-old student and South Londoner, Aisha, believes young men especially have to ‘stick together’ during another wave of #metoo. “It’s almost to prove their loyalty towards each other by defending the actions of each other, which like in this situation and many others I’ve witnessed seems to stem from the glamorisation of gang mentality, toxic masculinity and this fear that the ‘feminazi’ will get them.”

Nowadays, there’s also the argument of being ‘cancelled’. That men are too quick to be judged by their poor actions and that generationally, our ‘snowflake’ feelings are being too sensitive. When in fact, domestic violence soaring during the lockdown is an example that rape isn’t something that happens to scantily-clad drunk women who are ‘asking for it’. According to Rainn, 93% of minors are assaulted by someone they knew, with 59% of assaulters being acquaintances, 34% were family members and 7% were strangers to the victim.

‘Bro code’ is key in perpetuating rape culture. This solidarity between male friendships has in the past been linked to men covering each other’s back when it comes to infidelity and essentially, behaviour which hurts their partners. Yet bro code is also the accepted safety net that keeps accountability at bay. It makes men feel as though they are not a part of the problem.

“Every girl I know has been assaulted by someone she is friendly with or who is in the same friendship group and in one instance a family member,” says Grace Peutherer, 24, based in Dublin. “So men must know that their friends exhibit this kind of behaviour because they’re around them all the time. Sometimes I think that they try to disassociate themselves with it because they know that it’s wrong and they don’t like to believe that they can be mates with a person who would assault women.”

Among our friends, regardless of gender, there’s this unsaid rule of commonality and mutual understanding. There’s this belief that birds of a feather flock together, so if men were to confront their friends about crossing the boundaries of consent, they’d have to also look introspectively while questioning their chosen circles. This emotional intelligence isn’t something we’ve taught men and boys to do, and frankly, isn’t something many people want to do, period.

“Men socialise in a way that permits them to speak about women dangerously,” says Shazana, a start-up founder and mother of two based in London. “To use and hide behind terms like ‘frigid’, and ‘cock-tease’ and so forth, is to admit and face that their engagement in the banter is to give up their violent positions over women and our bodies.

“Their language about sex, women and relationships is rooted in violence, self-service and entitlement. So they are definitely around rapists and sexual abusers but may laugh off the guy as ‘eager’, ‘on it, or ‘has game’. Men encourage the rapist in the group to continue the behaviour by not engaging in [those conversations]. They are allies to rapists. Men know but women have to explain what’s happened to them, away”.

And so many men, because they may not share nudes in their group chat, or discuss groping women, believe they are not a part of the problem. Too many men class themselves as the ‘good guy’. This is because another facet that allows rape culture to thrive in this singular image we have taught socially on what it means to look like a predator.

Men who are abusers are supposed to have drunk too much. Men who don’t respect women and say explicitly sexist things. Working-class men. Men who have archaic thoughts such as ‘women shouldn’t work’, or ‘women are too emotional’ or shouldn’t get paid as much as men. Both women and men are not taught to see abusers as those who can be attractive, kind or intelligent, especially when violating you.

Not men who play video games with their female best friend and are unapologetically feminist online. Not men who will retweet #metoo ‘win’s. Not men who read intersectional feminist literature. Not men who shout “Black Lives Matter!” and quote the pink version of clitoral rights. Not men who like to give head. Not men who can recite the definition of consent. Not these good men.

When in fact, as 26-year-old East London based journalist Faima Bakar puts it, “we’re in a sexual assault pandemic. That’s what’s killing us.” But are we really looking for the cure? What is the antibiotic for those who go through sexual assault and after the assault?

London based 34-year-old producer, Renasha Khan, makes the point that that “though there have been ripples of social changes due to #metoo, there have been no structural changes have taken place in order to protect women and ensure safeguarding for victims.”

Rape culture persists, at all levels because the violence done disproportionally towards women is not seen enough as a criminal activity. From cat-calling to inappropriate touching to unwanted and persistent attention in the workplace, rape culture is bursting at the seams of society. “This chasm isn’t an accident. It’s symptomatic of a society that upholds and normalises rape culture and many men aren’t aware of this because a lot of the time, they’re the perpetrators and beneficiaries of gender-based sexual violence,” notes 24-year-old multi-media journalist and host, Diyora Shadijanova.

Maybe it starts off by truly understanding that there isn’t a template cut-out to determine what it means to be an abuser. That just because you don’t think it’s abuse, doesn’t make it any less so. Just because you’ve been abused, doesn’t mean you can’t inflict it onto another person. More importantly, it’s dismantling this idea that anti-violence work is not women’s work. So in simple terms, your boys are definitely to blame and your silence is complicit. It’s no longer extreme to say, it’s killing us. It’s killing women.