February 2020

I was in my hometown of Doncaster, about to embark on what turned out to be my last night before lockdown. I’d come home to support a friend’s boxing match and knew before I even pulled off the motorway that after a few pints, I would be easily persuaded to go on a night out in the one place I feel the most unsafe. It will be okay, I reassured myself, you have your safety plan. I was with my best friend, an ally who I trusted to be equally as informed and prepared as I was. It will be okay, I reasoned with myself, weighing up the math. According to my clumsy, tipsy calculations the probability of anything bad happening would be minimal, my safety plan ensured that. For the past two years, since fleeing an abusive relationship, on the now scarce occasions that I would frequent my hometown for a night out, we make sure not to go to certain bars, ensuring our route from bar to bar avoids any areas of risk. During the night, we use coded language to communicate my levels of unease: a squeeze of the hand or a knowing look that says it’s time to move on. On our way home, we avoid certain takeaways, and we don’t use the normal taxi rank to avoid being followed home. And, if I really don’t feel safe, in the events of a panic attack, I have my mum on standby to pick me up in a moment’s notice.

This carefully laid out system is imperfect. It doesn’t offer me the safety and security and peace of mind I wish I had: the protection of a restraining order which was dismissed when I begged the police for one 6 months prior. My perpetrator is still able to walk the streets without consequence. I don’t know if my abuser was out that night, we didn’t bump into him or run into any harm, and this is solely down to my vigilance and safety planning. Was my night less carefree as a result of having to constantly look over my shoulder, my body being rigid and tense, on edge all the time? Yes. But I managed to find a way to enjoy myself, and most importantly, I didn’t stay in all night paralyzed by fear whilst my abuser monopolized the sense of freedom in the town. He didn’t win.

June 2020

The lockdown rules that felt so oppressive over the past few months were beginning to lift, and whilst we may now reflect on its prematurity, at the time there was a sense of relief for most. Particularly for survivors of abuse and assault, the lack of control, agency and access to healthy coping mechanisms and support systems presented unprecedented triggers which we weren’t prepared for. For those locked down with their abusers, it presented an imminent risk to physical safety with a 60% rise in calls to domestic abuse helplines in the past year.

We looked at the reopening of pubs and restaurants as a symbol of hope, yet I still felt a sense of uncertainty when it came to going out. I recognized that the probability of my abuser finding me whilst on a night out was a lot lower this time. I fluctuated between trusting my instincts and crippling doubt. I wasn’t in my hometown, but I was only 15 miles away and we have a lot of mutual friends in mutual venues. The likelihood that both my abuser and I would book the same restaurant, on the same day, during the same 2-hour time slot was extremely low, but what if we bumped into him on our way from one place or another, what if one of his friends saw me and told him my location. The risk was less concentrated, more widespread during summer, yet I still didn’t feel safe.

December 2020

Boris had just announced that Christmas would be cancelled. Politically it was infuriating, a reminder of the incompetence of our government, and personally I was riddled with anxiety as I, like the rest of the nation, scrambled to find a way to not spend Christmas alone. Despite this, I felt a huge sense of relief, at the realization that Christmas was going to be safer this year. I always feel a mental tug and pull as I wrestle with the social obligation to attend the annual week-long bar crawl that occurs each Christmas. Since going to university almost 10 years ago, our childhood friends have congregated in our hometown to reunite on Mad Friday, Christmas Eve and Boxing Day. It was always something to look forward to, but has now become a stress-inducing, physically unsafe tradition.

It’s a time when my abuser can rightly assume that I will be in his vicinity, and he’s used this emotionally charged period to find me, like a hunter stalking their prey. One Christmas, after seeing me get out of a friend’s car, I was bombarded with a deluge of messages which ranged from begging to see me, to angry threats promising that he would find me, and he did. With my night ruined, I, for reasons now unknown to me, chose to walk home. “I can see you” the messages said as I received pictures of myself walking home, proving that he was behind me. My pace quickened but he caught up with me nonetheless. Squeezing me by the shoulders, he pointed to the roundabout ahead that read ‘Welcome to Doncaster’ in overgrown hedges, and told me what he intended to do to me. I do believe he would have raped me if a girl he’d cheated on me with months prior hadn’t rung him, giving me the opportunity to run away.

Whilst the nation was in mourning of the ‘normal’ Christmas that could have been, I was silently relieved to have had that risk removed. Not by the police, not by the criminal courts, but by a virus of all things.

May 2021

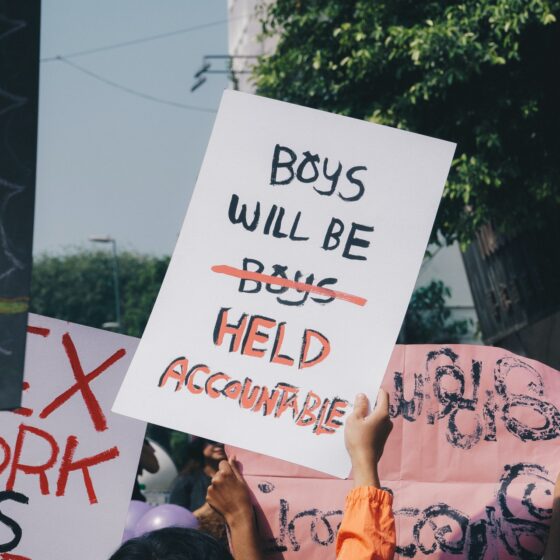

Sitting in a beer garden, coats pulled tight, fingertips numb as we grasp icy pints in the springtime breeze has come to represent freedom for so many. As a survivor, I haven’t been able to harness the same carefree excitement. When Boris’ ‘Roadmap out of Lockdown’ was first announced, I noticed a sense of unease in myself. This was then compounded when Sarah Everard was brutally murdered, a harsh reminder that we as women and marginalized genders are not safe even in a lockdown when the streets are less populated. Now our streets have been newly transformed into alfresco dining zones littered with drunken men, and opportunities for our safety to be violated, and it’s terrifying.

It’s for this reason that I haven’t rushed back into post-lockdown life. Even though I am craving a freshly pulled pint of the cheapest lager on tap, I’ve approached this easing of the rules with extreme caution. The fact that my friend is planning a reunion in our hometown in celebration of her birthday next weekend is putting my resilience to the test. Our group chat is buzzing with excitement, littered with outfit choices and meticulously organized table booking schedules, yet no matter how much I want to, I can’t seem to tap into that level of joy. This is the first time since lockdown began that I’ve had to properly prepare myself for the risks associated with my hometown, and I feel unprepared. I’m out of practice. My carefully ironed-out safety plan has not been tried or tested in over a year, and I can feel myself becoming hypervigilant in order to protect myself.

In the past year, when we have looked forward, our attention has been focussed on how life can go back to normal. This is not an uncommon state of being for survivors of abuse and sexual assault. We’re told that life has to go back to normal, that society doesn’t adapt to accommodate our needs. Our streets don’t become safer, we must learn to navigate them more safely. We must be malleable, mould our healing in a way that allows us to participate in a society that doesn’t protect us. We must move on from our trauma, just as we must move on from lockdown. But how can returning to our old way of life be something to celebrate when it saw 97% of women being sexually harassed, 1 in 4 women abused by an intimate partner, 1 in 4 women experiencing rape or serious sexual assault, and two women a week murdered at the hands of their partner or former partner each year? Survivors want safety more than normality and we haven’t been guaranteed this, so we protect ourselves as best as we can. We go out for a pint armed with our carefully laid out secret safety plan and hope for the best. This isn’t a society we should be returning to.