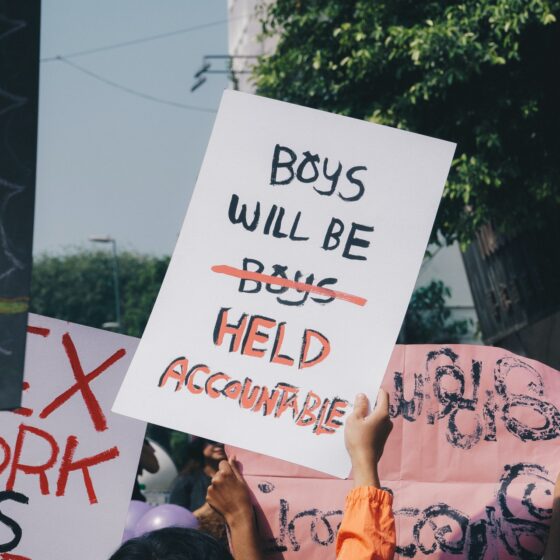

When it comes to conversations about violence against women and girls, disabled women are often left out of the discussions. But we are the group most at risk of experiencing—and being trapped in—domestic violence situations and environments.

I used to be in an emotionally abusive relationship. My ex-partner used my disability and my illnesses against me by telling me that nobody would want to have kids with a disabled woman and making me feel like a burden to him because of my needs. He made me feel worthless, and I believed him. The manipulation and gaslighting was so severe, it wasn’t until months after we finally broke up that I realized he’d repeatedly sexually assaulted me on top of the emotional abuse.

He made me feel worthless, and I believed him

It was the toughest relationship of my life to get over. When I first moved back home, my mother would often have to sleep with me because I had such horrible nightmares. I doubted my own memories and experiences so much that it almost led to a mental health breakdown. Through my family’s strength and support, I was able to seek help from a therapist and began taking antidepressants.

My story, unfortunately, is not unique to me or to the disabled community. Disabled women are one of the more vulnerable groups of people in society, thus becoming easy targets for being taken advantage of. But no one is talking about it.

In 2018, the UK Office for National Statistics Crime Survey for England and Wales found that disabled and chronically ill women were almost three times as likely (17.3 percent) to experience some form of domestic abuse than non-disabled or chronically ill women (7 percent). A study on VAW.net found that in the US, disabled women have a 40 percent greater chance of intimate partner violence than women without disabilities.

“The ongoing trauma of abuse, compared with a world that is already pitted against you can make it very difficult to move forward,” Psychologist Şirin Atçeken said. “It is harder to find a job, seek support, move, access financial help, and, for many, options are very limited, so they often find themselves in a cycle of abuse with no way out.”

Data from SafeLives reveals that disabled people typically experience abuse for an average of 3.3 years before accessing support, compared to 2.3 years for non-disabled people. Even after receiving support, disabled victims were 8 percent more likely than non-disabled victims to continue to experience abuse.

A big reason disabled women stay with their abusers for so long is because they are often their caretakers, too, and as abusers often isolate their victim, they may be the only support left.

“What differs [from non-disabled victims] is the realistic opportunity to escape,” says leading barrister and advocate Paula Rhone-Adrien. “And then to remain safe from the perpetrator of abuse who the disabled person may be reliant on for travel, maintaining their health and other welfare requirements, and who has often made themselves indispensable to the victim.”

Dr. Rebecca Fish, a researcher at the Lancaster University Center for Disability Research agrees. “The abuse might be experienced differently because there is less support, certainly fewer accessible services, and people often don’t believe disabled women because of the negative media accusing them of ‘scrounging’, which is a derogatory term for a ‘freeloader’ or ‘moocher’.”

Unfortunately, being the carer also gives the abuser more opportunity to abuse and control their victim. One way they may do this is through financial abuse.

The current disability benefits system in the UK takes the income of every adult in your household into account, so most disabled people who live with partners can’t claim disability benefits. This leaves them dependent on a potential abusive partner for money. In turn, the abuser could use finances as a means to control their victim. If they left the situation, they would qualify for benefits, but they can’t leave if they don’t have any money.

Due to my abusive ex’s income, I didn’t qualify for disability benefits, and he used the situation to control me financially. I paid the rent from the other small amount of benefits money I received that wasn’t determined by household income. After paying rent with the little money I did have, I was left with barely anything. My ex did give me money, however, and it was to do the grocery shopping, but more often than not, he’d spend that on weed or alcohol before we could put food on our table. If it wasn’t for my parents allowing me to return home, I would’ve been trapped with an abusive partner, because I couldn’t have afforded to leave him on my own. I’m lucky that I had family who could take me into their home, as it’s also harder for disabled women to leave an abuser because there is less support available for women wanting to flee and seek safety. A BBC investigation found that just 11 percent of domestic violence shelters are accessible and equipped with the necessary accommodations for folks living with various disabilities such as blindness, deafness, and wheelchair use.

“There needs to be a dedicated contact for all disabled people that is published widely and accessible in each area,” says Dr. Fish. “Housing and domestic violence services should be made aware of these specific experiences [from disabled folks].”

Most importantly, disabled women should remember that there is a way out and you are strong enough to take back control of your life, even when your abuser and society tell you otherwise.

“Being disabled isn’t the reason why you are suffering from abuse,” says Paula Rhone-Adrien. “The perpetrator may tell you it is, but that is not true.”

You do not deserve your abuse. You are not a burden. And, most importantly, you are worthy of love, support, and help.

If you are a disabled or chronically ill woman experiencing abuse and seeking help, please contact: