I have a complicated relationship with the hashtags of the #MeToo movement. When it first started, I wasn’t in a place where it was safe for me to tell people about what had happened to me. I was happy that a conversation about these issues was starting, but I was also envious of the ability of other women to share their lived reality. I was one of those who just couldn’t post “#MeToo.”

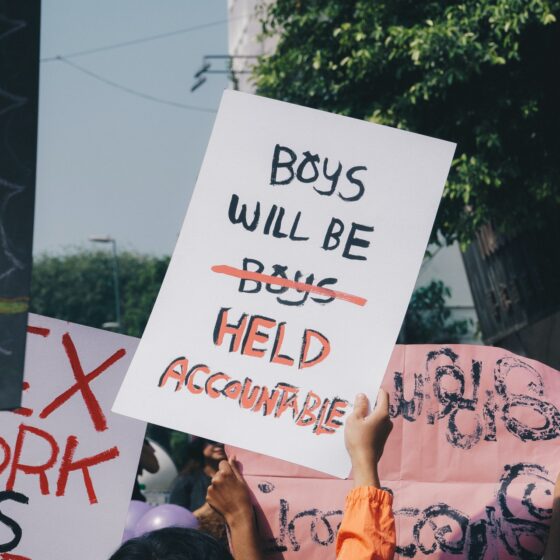

Now, after Harvey Weinstein’s lawyer’s ignorant and offensive claim that she “would never put myself in that position” when asked if she had ever been sexually assaulted, there’s a new hashtag doing the rounds. #WhereIPutMyself is what women are using when they share the environment in which they were sexually assaulted. I applaud the women who have shared their stories in this manner. It is important that we describe the realities of sexual assault when faced with ignorance.

And yet, scrolling through the examples that a certain woman’s publication chose to share, I felt…bad. Ashamed even.

When I looked at the experiences listed in that publication while thinking about my own, I felt like I couldn’t share what I had gone through, too. The environments listed included churches, doctor’s surgeries and schools. Which is unspeakably awful. But they were all situations that spelled out a clear-cut narrative that I just…didn’t fit into. Or maybe I did, but something tells me that many in our society wouldn’t think so.

The “right” victim

When I was sexually assaulted, I was a freshman in college and in a boy’s dorm room. Drinks had been had, the environment was that of a sexualized college party scene, it was California… You can imagine it. I wasn’t a church-goer. I was a sexually active young woman who got trapped in a room with someone who meant her harm. But it was a dorm room, and I’d had a few drinks. I was on the cusp of adulthood and wearing (gasp!) a halter top.

There is no question that I was sexually assaulted, that I didn’t deserve it, and that it wasn’t my fault. But when I was reading through the tweets Monday night, five years later, I was made to feel like maybe, somehow, it actually was my fault. That I wasn’t the “right” type of victim. At least, not the type of victim that someone would use to quickly win a Twitter argument.

And despite the facts that I knew to be true, and the years of therapy that I’d been through, I thought, “I can’t share my story.”

In the environments that the publication chose to list, there weren’t any of those potentially grey areas: there were no women who thought that maybe they’d try to not be a third wheel at a party and so went off on their own, wearing a tank top and cut-off shorts.

So, my question is this: is this hashtag playing into what that awful lawyer was saying after all? The toxic narrative that some women deserve it, and some don’t? That if we do have a drink (or two or three), or if we are wearing ‘sexy’ or ‘revealing’ clothes, we are somehow at fault if we are assaulted? Is it helpful to use hashtags like this to quickly make a point, only to leave out great swathes of other women’s experiences? Are we thereby making anyone who doesn’t fit into that story feel that what they went through doesn’t count – or, god forbid, that they deserved it?

Is it helpful to use hashtags like this to quickly make a point, only to leave out great swathes of other women’s experiences?

Making every story valid

I don’t know the answers. But I do know how I feel, and I can’t help but think that there are other women who feel the same.

I strongly believe in the importance of women sharing their stories – all of them. I also believe that when we speak up about the injustices that have befallen us, or about those that have befallen others, the world gets a little bit better. That’s the point of Restless Magazine. As such, I don’t want to discourage the hashtags that make these conversations happen. But I am concerned at some of the unintended consequences of this world of hashtags, at who and what they leave out, and how it makes others feel.

When media outlets and publications propel these things to viral status, they need to be careful about how they shape the narrative. About the tweets they choose to include in their articles, the survivors they deem “newsworthy,” and the unstated implications of their articles. About the message that they send when they choose to not write about other people’s experiences.

When media outlets and publications propel these things to viral status, they need to be careful about how they shape the narrative.

No, you can’t please everyone, and you can’t speak to and about all people, all the time. But established media outlets in particular should all take the time to make sure that they cover the #MeToo movement, hashtags and otherwise, in a broadly inclusive way before they press publish. After all, as journalists are taught, it’s often what you don’t write that makes the biggest impact.