I’ve always lived in fear of pulling together a rushed outfit that reveals my lack of style knowledge, so I routinely prepare the day’s outfits the night before, right down to my sock selection. But as I started formulating my look for the next day’s appointment, I realised my laundry was the latest on a long list of rituals I’d let dwindle in the midst of PTSD recovery.

My favourite tees were heading for underneath the bed, amongst old takeaway boxes and my scattered collection of vibrators, and my comfort jumper (we all have one) was in the washing basket. In the midst of this chaos, I sat on my bed in my pants, breasts slumped on my ribs, faced with the weekly decision of what to wear to therapy.

I acceptingly felt the last bit of control I had leave me. Should I cancel the appointment and try again next year? In the grand scheme of my mental health issues, the decision of what to wear to therapy should be minute. But in my anxiety-crowded and roaring mind, the decision becomes monumental.

My first experiences of therapy were not a choice. Instead, they were a series of compromises, administrative procedures and even punishments. My first came when I was in school and was called to the headmistress’ office to be spoken to about attending a counselling session. I was confused, because although my mental health problems were causing me to dissolve like a migraine tablet in water, I thought I’d done a good job of concealing it. When I got there, a girl named Maria was sat looking desperate for comfort, blinking up at me. My teacher told me I was sitting in on her counselling session as a friend, but I’d never spoken to her before. Without hesitation, I spat ‘But I’m not her friend’. It later turned out that I was simply the only person in our class who hadn’t bullied her, so I put up, shut up, and endured fifty minutes of counselling that had nothing to do with me.

Although at the time I felt angry at having to be there, now I sometimes wish all my therapy appointments were assigned to me without warning. Largely because I wouldn’t worry so much about what to wear. Of course, that day, I’d had no choice but to don my school uniform: a knee length skirt I’d adjusted to be not-so-knee-length, a royal blue jumper, and a blazer with a flying horse printed on it.

The second time I went to therapy, I punched my bedroom wall so hard afterwards my knuckles cracked and my fingers bent. Then I hit a person in the face. I was 15, and I wanted my therapist to give up on me within the first few minutes of our session. I wanted her to know she couldn’t win, so I wore an extra inch of eyeliner. I slipped on a tiny skirt with thigh-high socks, and teamed them with a heavy black hoodie, pulling the sleeves right down to my fingernails. I refused to talk throughout the entire session, wearing the smirk of a mafia criminal with a very expensive lawyer en route.

A short while later came what I’ve coined the ‘administrative procedure’ therapist. After reporting my sexual assault to the police, I attended a compulsory counselling session. Wanting to be believed meant I attended enthusiastically. This was the first therapist I’d met that I felt I actually needed something from. I required confirmation from her that I’d been hurt – which I had been – to pass on to the police. Thus began my carefully curated counselling look. Unknowingly, this cemented what had, and would continue to be, a tradition. A ritual, even.

The shock of the event hadn’t even hit me yet, so I actually felt a version of fine, but I spoke more about the trauma I felt lurking deep within to try and show her the truth of what had happened to me. I wore the kind of distressed cardigan with loosened threads that a female failed-journalist-turned-alcoholic would wear in a Netflix series, left my nail varnish chipped and reminded myself on loop not to apply make-up that morning. I was aiming for dishevelled, assaulted – something I now know is impossible to emulate, there being no specific look to someone who has been assaulted. I tucked my knees up under my chin as I chatted to her, and made sure to cry where appropriate.

It didn’t work, and I didn’t feel that I got anything out of that session. So, I stopped seeking help.

Five years later, roughly where we are now, I referred myself to psychotherapy as a matter of emergency, and the same detrimental problem arose. What was I going to wear? It felt shameful to show skin, so any vests, skirts or V-necks were out of the question. Survivors are painted with the ‘liar’ brush so abruptly that there’s an overwhelming pressure to make your every action, thought and behaviour contribute to achieving belief from others. I never stop feeling like I’m on trial, even though the perpetrator didn’t get one. Surely I couldn’t go to therapy for sexual violence related PTSD with my legs showing?

My first idea was to wear no nonsense clothes. Seamless jeans with a perfect fit, a pristine white blouse and boots with sensible heels. The kind of clothes my mum wore when she had me, so she wouldn’t look so young.

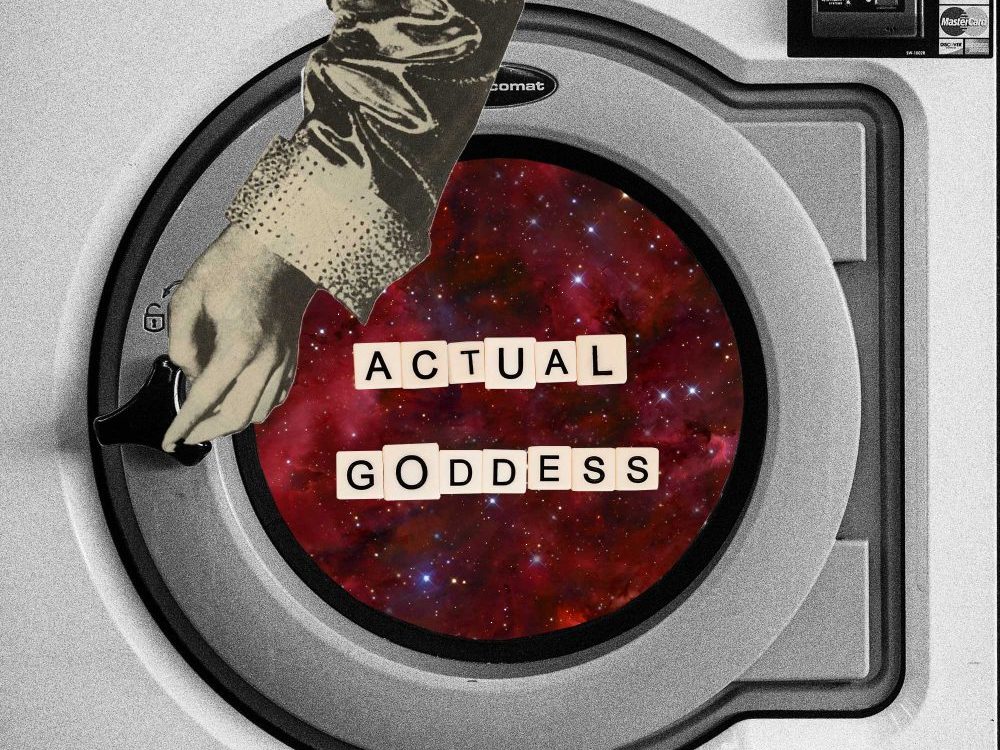

In the end, on that Monday, I wore ripped black jeans and a cosy t-shirt with a renaissance style painting print and ‘Actual Goddess’ written in red across the chest. In the middle of the session, I began to feel uncomfortable. I thought my therapist must be judging me, judging my outfit, diagnosing me as a narcissist because of the cocky slogan. Or maybe she thought I was empowered because of it, and maybe she found that odd for a survivor. I worried I might be perceived a liar once again.

But I was wrong. It ended up being the best session I’ve ever had. I opened up about my anxiety, my flashbacks, and the undeniable issue I have with shame and vulnerability – clearly manifesting through my inability to dress fearlessly.

I’m always worrying about how other people read me, especially as I’m always trying to carefully frame my own portrayal and ‘sell’ my own truth. It’s inevitable that those who go to therapy will worry about their presentation – it’s an extension of the shame stigma that’s been built around mental health issues, and what we wear has a lot to do with that. Dressing for therapy amplifies the insecurity of worrying about what others think of us, because therapy is the place we go to be our most vulnerable. But what I’ve learned, with the help of therapy, is that vulnerability is okay. It can be wonderful, beautiful even, and losing control, even sartorially, is a first step to being open with your therapist. Tomorrow, I’m throwing on a red and white striped top everyone says is my most ‘me’ item of clothing. And I’ll be okay.

Artwork by Esme Rose Marsh