When I was 15, I told my Nigerian mum I thought I was depressed. She told me to pray.

My teenage pleas for help were unknowingly wafted away by my parents’ loving but disregarding hands. As a result, I slowly but surely began to grasp the lay of the land when it came to attitudes to mental health issues within my religious Nigerian household. It consisted of: “Yeah, you don’t have them”. Sadness? Rebuke it. Stress? Pray it away. Depression? Well, that’s exclusively for the whites. That’s just the way it was, and I could never really harbour any blame towards them for it. Because I know their reaction wasn’t borne from a deficiency of love and care – rather, it was the opposite.

I’ll never forget the day when my dad sat me down on our tin-coloured carpet stairs. I was in year seven when I first witnessed the genuine flakes of fear rusted around his perennially-furrowed brows. Not knowing who to turn to, I had initially told my sisters about the suicidal thoughts and the feelings of isolation that had gripped me. News made its way back to my parents and my exasperated father, none the wiser on what to say at that moment, desperately tried reassuring me of all the good things that surrounded me. Namely, the love of my family and, more importantly, of God. I could see he couldn’t bear to see his pre-pubescent daughter in the throes of something he couldn’t quite grasp. The candid moments that me and my dad shared that day have left an enduring sheen of care over his flimsy implorations to pray later down the years.

The generation divide

The prospect of mental ill health is, for a lot of African parents, as utterly beyond their scope of understanding as it is terrifying. To this day, my dad occasionally mentions the confusion and helplessness he and my mum endured during that time in my adolescence. It’s clear to me now, in hindsight, that their crass appeals for prayer weren’t intended as a proverbial plaster, as much as they felt like it at the time. Their textbook replies to my outpourings of emotion were, more often than not, simply them trying to level with me.

Consequently though, through no real fault of their own, I ingested a fat pill of guilt. If I could choose to pray and rebuke sadness, if it was truly that quick of a fix, why didn’t I opt to do so? Why would I willingly choose to distress my parents? Surely, I could just put it to bed? Growing up being told to just stop being sad created crevasses within me that filled up with guilt when I had depressive periods. However, contrary to all this, the effects of being raised in an environment that vehemently rejected depression also doused me in denial. Occasionally, there’d be times where I’d express feeling sad for no reason and, in response, I’d get a chuckle and a casual anecdote about abject poverty in Nigeria. I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve heard: “You don’t have to walk ten miles to fetch water, Tide, you don’t even know what sadness is. You’re lucky!”. As a result, my inbuilt barometer for self-denial over my mental health struggles is off the charts hunny.

For years, I’d tell myself “Tide, you are fine. There’s nothing wrong with you… Yes, you haven’t left your room in days, your eyes are bloodshot, and your heart is threatening to rip itself out of your chest. But you are fine. Pray.” One of the lasting effects of this sort of upbringing is that it makes you second guess yourself almost constantly. For years, those two pillars of thought warred against themselves inside my head. I’d be feeling guilty for feeling depressed then, two seconds later, I’d convince myself that I was just being stupid, that, obviously, I was fine. I am still getting to grips with understanding you really don’t have to be subjected to the level of external suffering held up as an example by my parents in order to suffer within the confines of your head.

A cultural norm

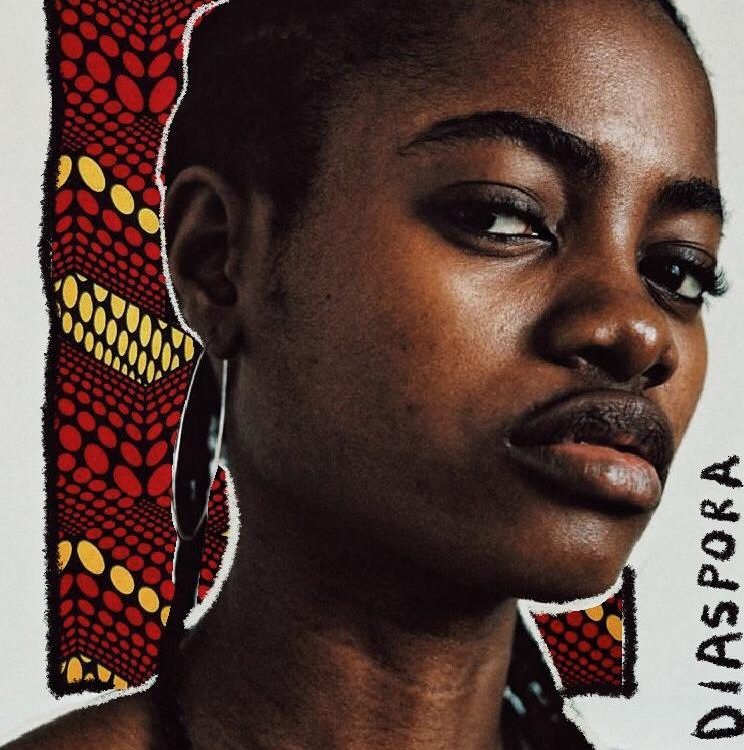

If you take the time to poke and prod into the lives of those in the African diaspora, you’ll most likely bump into similar anecdotes. There is a floating misconception, widespread within African culture, that mental ill health is a wholly spiritual ordeal – with the antidote being a swift swig of prayer – or just a fallacious lie, concocted by overly-emotional westerners who don’t have real problems beyond the fact they simply don’t know how to pray. This is a massive issue for the diaspora’s offspring to navigate. Because on one hand we are meant to be derived from this lineage of tough, resilient and pliable people, elders who have been through the unspeakable but still keep going, stoically standing upright through onerous times. But, my God. We are still humans, as fragile, soft and squidgy as any other. And it’s painful to see our parents, the first generation, having to suppress that to survive.

And is does seem like that’s exactly what they’ve done to get through life. Traversing through challenging childhoods, migrating across oceans to be met with rancid racism to get to their here and now. I’m sure my country of birth, Nigeria, has a mental health epidemic. However, stigma still potently exists there when it comes to showing weakness. Additionally, for those living in poverty, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs explains why they may not be as explicit about their struggles with mental health – they need to focus on fulfilling their most basic needs first.

There is a song sung in most Nigerian churches that goes:

“Prayer is the key, prayer is the key, prayer is the master key.

Jesus started with prayer and ended with prayer

Prayer is the master key.”

There is no doubt that prayer can be a sacred and deeply personal part of one’s lifestyle, and if you are religious and are struggling with your mental health, I’m sure prayer can be the key for you. Just as long as it also unlocks the door to your therapist’s office.