At the age of 24 I stood, loosely wrapped in a surgical gown, shaking with fear and low blood sugar, in the middle of a stark blue room.

My doctor drew lines across my chest and I shivered under the pen. The marks looked meaningless as I gazed down at them glassy-eyed, but I knew that’s where I’d be cut – sliced open. Exposed.

In mere minutes parts of my body would no longer be my own; they’d be sitting on a metal table next to me.

I was on the highest peak of the rollercoaster, at the point when you look down and think, “Oh, I don’t want to do this anymore.” But it was too late. I was there, and as terrified as I was, I also felt sharp pangs of hope that overshadowed the nagging doubts. After all, I wanted this – fought for it tooth and nail. I’d spent endless hours with specialists, on the phone with my insurance provider, saving money, working double shifts… all for this.

I had come to hate my breasts. So much so, that I wanted them taken away.

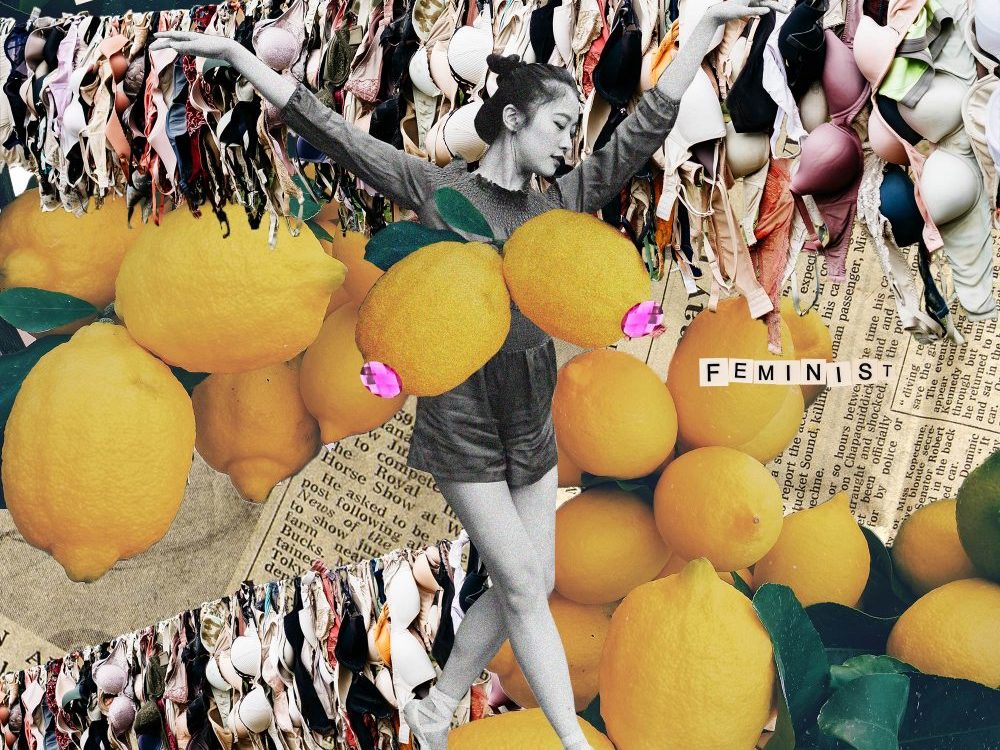

Now, in my 30s, I’m left with the question: Did changing my body in an attempt to feel safe make me a bad feminist? And did it actually make me any safer?

There’s nothing inherently anti-feminist about plastic surgery. It can be a life-changing, empowering pursuit. It can be a joyous awakening, a glorious physical emergence of one’s inner self. But that’s not what it was for me. It was a finish line to which I raced, because once I reached it, I believed everything would be okay. At some point during my young life, surgery had become the solution to a problem I didn’t fully grasp.

Being catcalled is a common shared experience for many young women and girls. There are endless threads on Twitter where stories are swapped, their similarities echoing into a bottomless void of trauma and harassment. It’s simultaneously comforting and distressing to realize you’re not alone. And it made me wonder, if I knew I wasn’t alone back then, would I have still come to resent my body with the same intensity?

I, too, have vivid memories of walking to the store to get snacks with my friends only to be hollered at by passing cars. I was in middle school and I’d hit puberty early. I was thrust into a body I didn’t know how to operate, a body I didn’t understand. Because I was just a little girl and I wasn’t aware of how my body was interpreted by others, the permission it seemed to give to strangers. I was 13 and suddenly hyper-aware that my body had betrayed me.

Middle school was just the beginning, and my large breasts and wide hips invited all sorts of commentary. It seemed everywhere I went I was public property. Older men made comments, sometimes other girls touched me. There was an assumed consent that surrounded me like a shroud, and it made me withdraw.

Quickly, hiding seemed the only safe option. I donned over-sized t-shirts, never wore tank tops or bathing suits, and did everything I could to shrink myself. I hunched my shoulders, pulling my chest in as much as possible. I held cardigans closed and kept my hands in front of me, hugging my body, hoping to go unnoticed.

Hiding is a skill that’s honed and cultivated. It’s also a habit that’s hard to break, and it became a default. I was often described as quiet – studious. I was the “shy” one in groups of friends, happy to let others shine. But it felt like a mask that was suffocating my true self, because I wasn’t shy. I was loud and goofy, a reliable leader in dire situations. I had trained myself to be anything other than that though, and without conscious knowledge of it, I simply became that withdrawn person.

After a while I leaned in to covering up and tried to find peace in the knowledge that the comments were out of my control. I couldn’t stop them, or the shame they made me feel. No amount of retreat would ever be enough.

But the sweet release of a reduction shone like a guiding light. If I could rid myself of my traitorous breasts I could be the happy, confident version of myself I’d kept hidden. It makes me sad, thinking about how much I hated myself, the amount of blame I took on. It also makes me mad. How could I have ever believed removing a part of my body would change how others treated me?

My breast reduction definitely changed my life, and my confidence soared, but I never felt any safer. My clothes stayed baggy and I didn’t magically cast off my trauma. But I did begin to worry that I was a turncoat. I didn’t go under the knife to highlight my favorite feature, or as a form of rebellion. I didn’t do it in celebration. I did it out of fear, and hope that I could slip in, barely noticed, and live without examination. I resent 24-year-old me for not being stronger, for not puffing out her tank-top clad chest and being a badass.

It’s always been alarmingly easy for me to take on blame, and this situation has proven no different. I blamed myself for drawing too much attention, and then blamed myself for the way I tried to stop it. Maybe the problem isn’t that I upheld patriarchal norms by altering my body, but my willingness to take blame for something that was never mine to own.

I don’t regret my decision – my spine health increased with my confidence – but I do wish I’d fully understood how much of that decision was driven by the actions of those around me. And maybe, instead of wondering if I should have my feminist card revoked, my energy would be better spent dismantling the system wherein this type of harassment is normalized.